Blog

Treadle and Pedal Powered Grinders

People have been grinding materials to process food, smooth surfaces, and sharpen tools for tens of thousands of years. Archeologists have found ancient grinding stones, which are rough rocks typically used to process seeds and nuts, that date as far back as 30,000 years ago in New South Wales. Over time, of course, the ways people have operated grinders have changed dramatically. The earliest known illustration of a grinding wheel, which was operated by a crank handle, appears in the Utrecht Psalter, a 9th-century illuminated manuscript.

Grinding wheels didn’t become popular, however, until the 18th and early 19th centuries. As grinders grew more ubiquitous, and technology continued to evolve following the Industrial Revolution, people began to invent new ways of powering them. Looking through our collections at the American Precision Museum, this month we are going to take a brief look at treadles, pedal, and water-powered grinders, and how each invention improved on the one it followed.

When most people talk about treadle power today, they’re typically referencing Singer Sewing machines. These abundant household appliances, first patented by Isaac Singer in 1851, were almost universally driven by treadles, or foot pedals that moved up and down like see-saws, before electric models began to gain traction in the 1890s. However, using treadles to efficiently convert human motion to rotational energy began long before the 1850s, and it spanned far more applications than just sewing machines.

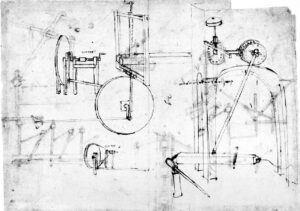

Leonardo Da Vinci designed, but probably never built, the first treadle-powered lathe around 1480. Treadles have also driven looms, mills, reciprocating saws, and, of course, grinders. In our collection, we have a treadle-powered grinding wheel patented by James L. Lord in 1854, pictured below.

Powering grinders with treadles was less efficient than using treadwheels, which were a kind of early treadmill, and capstans, which were vertical drums that workers would rotate. Treadles were fantastic, however, for more compact spaces, and if the torque requirements were relatively low, the treadle’s lack of efficiency wouldn’t be too much of a problem. Their main disadvantage was in their seesaw-like design. Treadles create power when people constantly switch between moving their foot up and down. This necessitates that they must stop their foot and lose momentum with each stroke.

The pedal-powered grinder, which first began appearing in the 1870s and 80s, helped remedy this problem without sacrificing the compact size of the treadle-powered machine. Someone using a pedal-powered grinder, like the one pictured below, could operate the device without having to stop every few seconds. Pedal power also allowed people to use the larger muscles in their thighs more effectively. This pedal-powered machine was probably homemade, which was relatively common. Pedal-powered machines have never completely gone out of use. Even today, some hobbyists continue to make them for home shops, and they are used in areas without easy access to electricity.

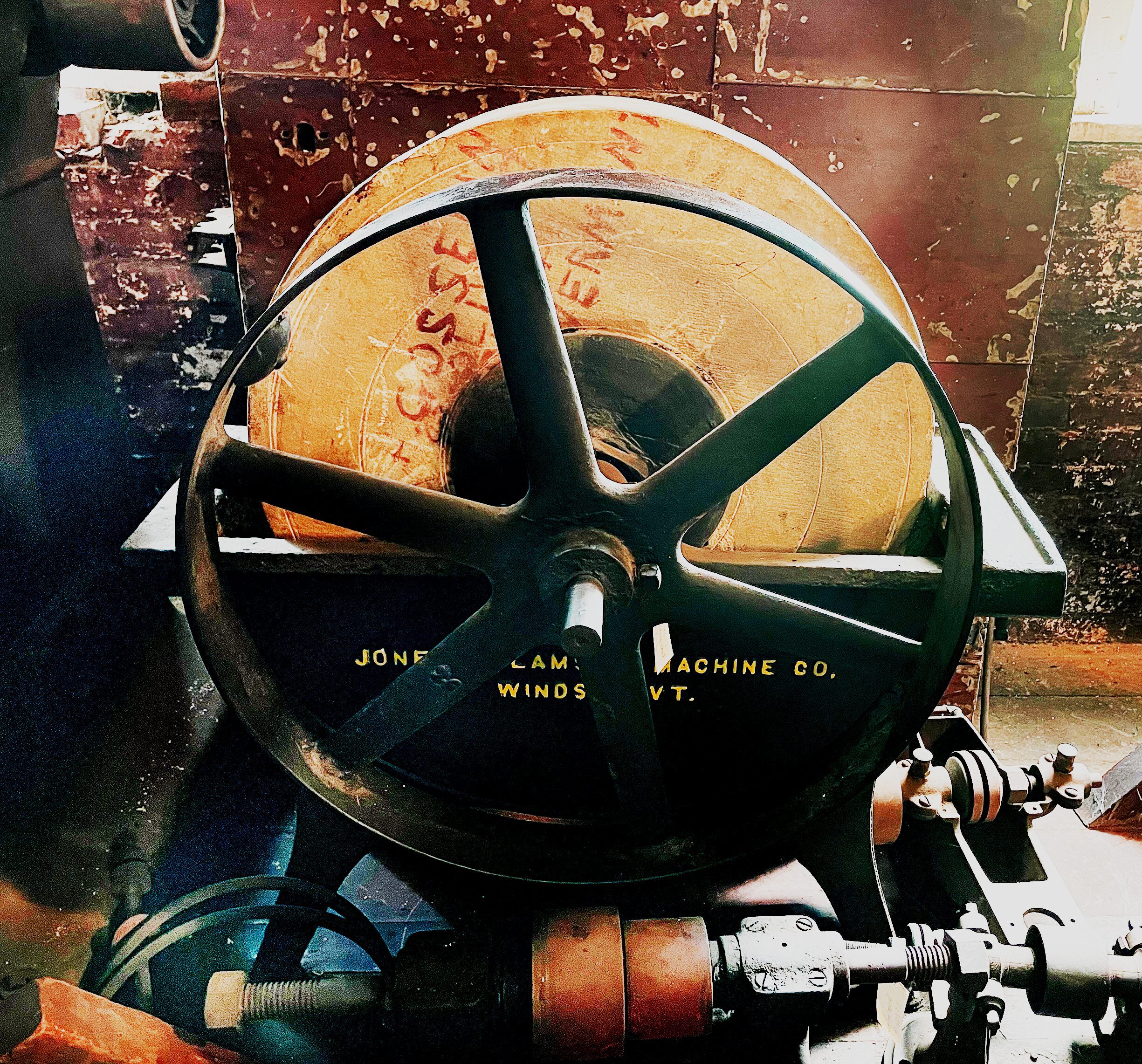

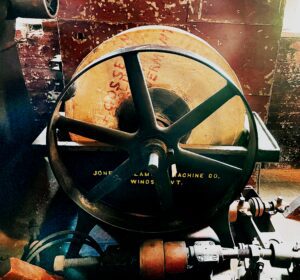

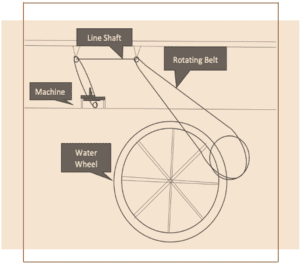

The last grinder from our collection today is a water-powered grinder from the Jones and Lamson Factory. A water wheel in the basement, connected by a series of gears and belts, would have powered the grinder upstairs. While waterpower was significantly more efficient, and it meant that individuals no longer had to power the grinders themselves, it came with its own shortcomings. Early waterpower was unreliable. In the winter, the nearby rivers would freeze, and in the summers, they would evaporate, leaving little to power the factories that hoped to use them. These limitations are what encouraged many manufacturers to transition to more efficient water turbines, and, eventually, steam power, which could be more reliable.

Today, grinders, which typically run-on electricity, span a vast array of shapes and sizes, and while some retain the circular shape that appears in the three historical objects above, others look far divorced from their predecessors. Despite these differences, it’s important to take a step back and realize that the basic idea behind these machines, using rough stones to smooth or sharpen material, has been around for millennia.

stay up to date

Want more content from the American Precision Museum?

Sign up to receive news straight to your inbox!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact