Blog

Tool of the Month: Hilliard’s Barrel Reamer

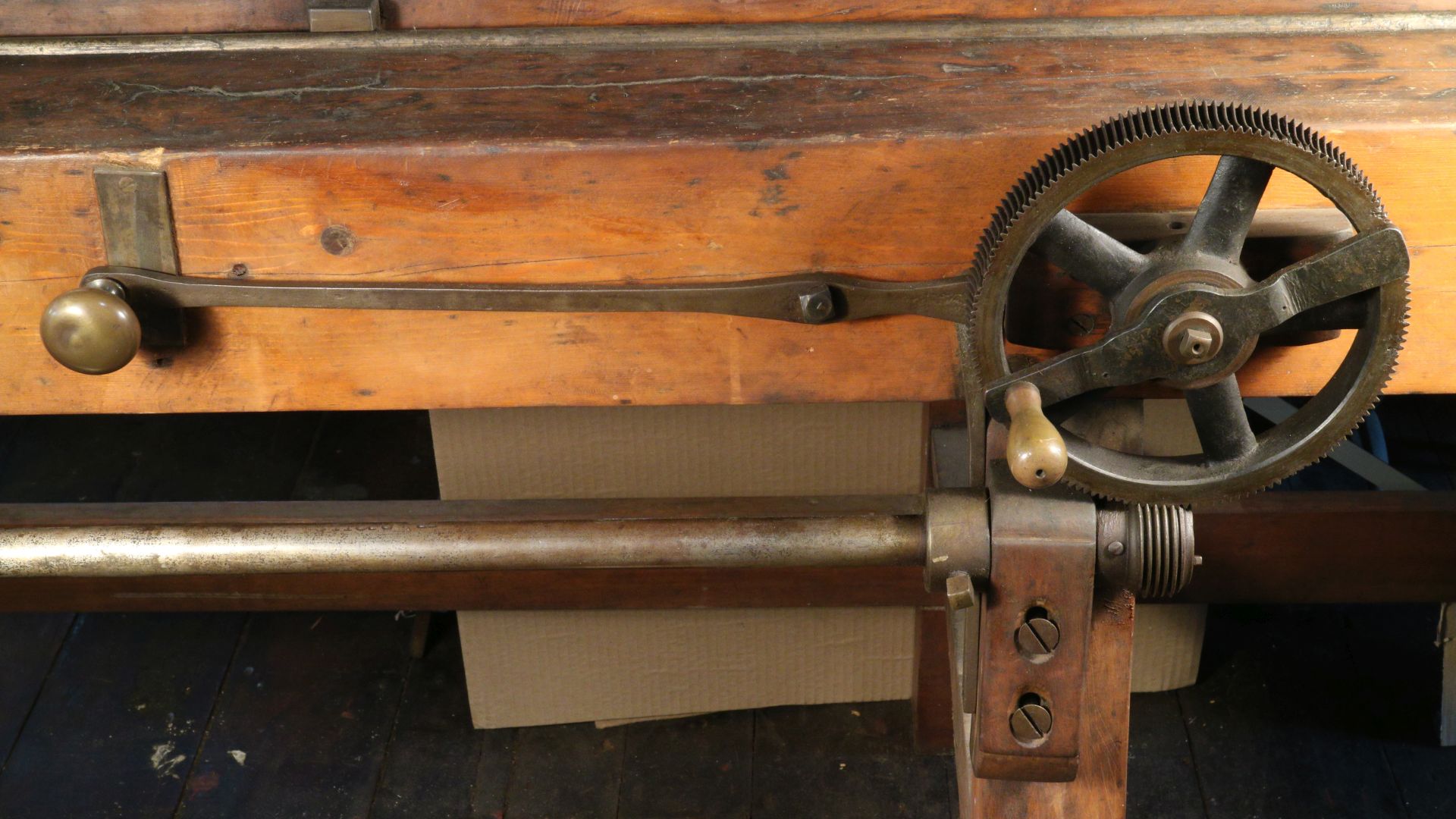

June’s Tool of the Month is a notable, locally-made machine. Even after well over one hundred years, this machine still looks good.

We don’t know who made the machine, but David Hall Hilliard (1805-1877) was the owner. He had trained with Nicanor Kendall at the Hubbard pump works and gunshop at the Vermont State Prison in Windsor. (Hilliard was not incarcerated!) In 1839, Hilliard went about 5 miles from Windsor, in Cornish, New Hampshire, to start his own gun shop.

Kendall married his boss’s daughter, Laura Hubbard, on September 2, 1835. David Hilliard (who was Kendall’s employee at this time) married a senior employee’s sister on September 10, 1835. The very close weddings seem to imply for the time that Kendall and Hilliard were close friends. In time, his sons, Charles and George, worked for him. After Hilliard died in 1877, his younger son, George, continued the business until around 1900. It would have been an operation that had changed much from the earlier times due to the introduction of all sorts of new technology since 1840.

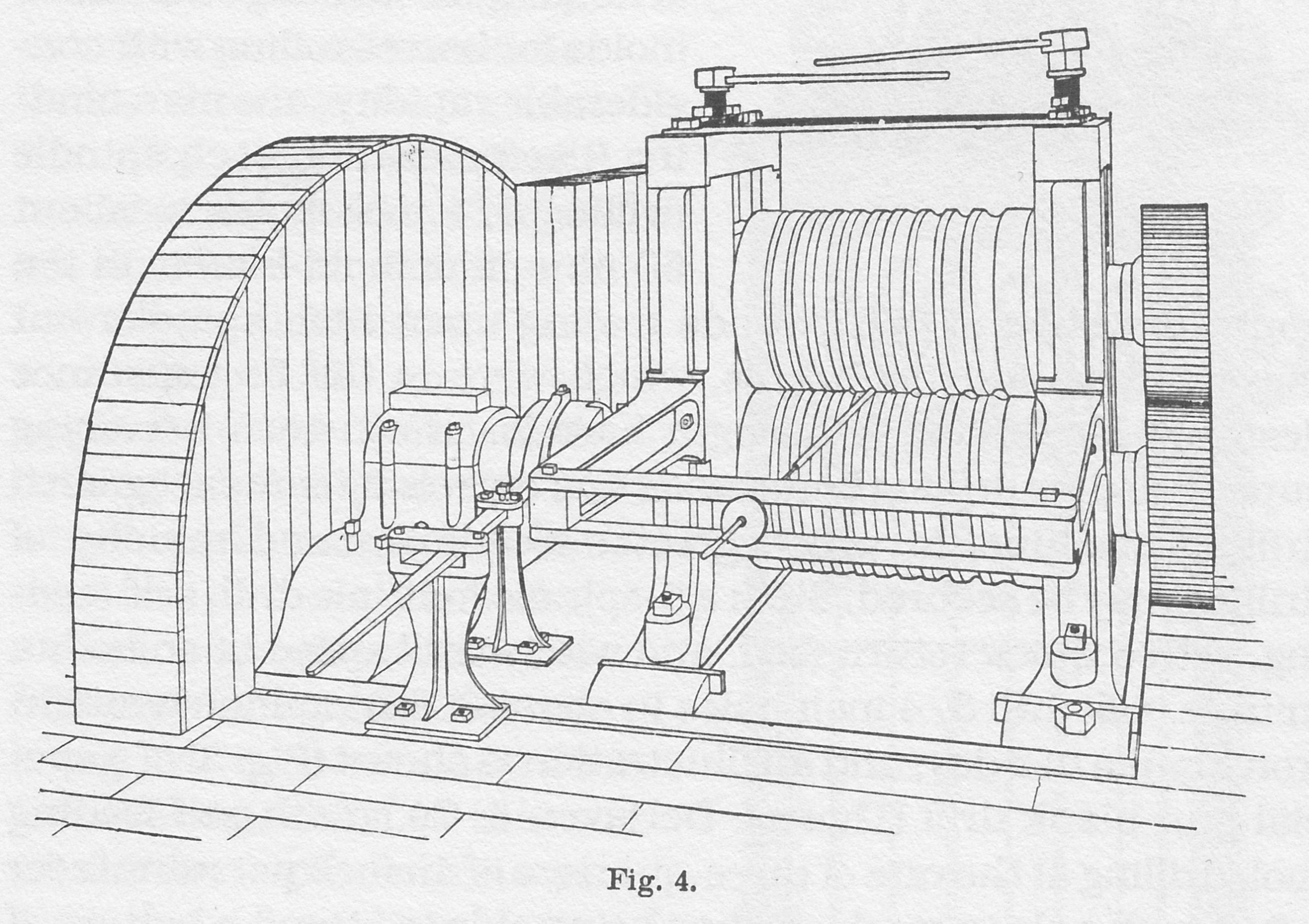

Here’s a drawing of a machine that did the work of making the flat piece into a cylinder and probably was used in the welding too.

Before the invention of the “gun drill” tool around 1890, most rifle barrels were made by taking a long and relatively narrow piece of iron, heating it, and wrapping it around a rod. They’d then “blacksmith weld” it to make a sealed cylinder that was open on the ends. Strictly large factories would have used this machine, which rural gunsmiths did not typically own. Gunsmiths in Cornish and Windsor got many of the barrels they used from Remington, way out of New York State. *Note that this doesn’t refer to a “Damascus” type barrel. Those had a twisted seam for the entire length of the barrel. This article talks about straight-seam barrels.

These barrels were satisfactory for use with what we nowadays call “black powder.” Until the end of the 19th century, it was just called “gun powder.” It was rendered obsolete by what we call “smokeless powder” for most purposes. Black powder operates at much lower pressures, so relying on a welded-together barrel wasn’t as problematic as it would be today. These barrels would have a smaller hole drilled through them than the final size. Most commonly, the gunsmith would be the one to finish the inside of the barrel.

This lathe was an important part of that finishing process. It was used to ream the barrel, make it smooth inside, and uniformly round. Wood just isn’t as stiff and stable as cast iron, but that was okay in this situation because the reaming cutter will follow the existing hole. Part of the smith’s training was to look through the smoothed barrel and recognize curves. If the result was not perfectly straight, the gunsmith would straighten it by bending in the opposite direction.

Our reaming tool on the machine looks very much like a twist drill at first glance. Unlike a twist drill, the tool has a square cutting end, which comes to something of a point. The reamer doesn’t have to cut the middle of the hole; it only makes a shallow cut on the walls and is much simpler to sharpen. Looking again, you might notice that the twist is “left-handed.” That is to say, the opposite of a conventional twist drill, or the lid on a jar, for that matter. But after all, it’s probably designed to cut by turning it “right-handed.” So why is that? Having the helix of the cutting tool be the opposite of the direction it’s turned to cut allows the cut-away chips to be pushed ahead of the cutter. The chips are pulled back out of the hole when using a conventional twist drill. The advantage of a left-hand twist / right-hand cut is that the bit is much less likely to jam in the hole. With right-hand twist / right-hand cut, the bit will act like a screw, and it may imbed itself so that the operator can’t get it out. In rural New Hampshire in the later 1800s, ruining an expensive tool like a long, specialized reamer was a very big deal. The square and pointed tool is likely another type of reamer. Among the few tools that belong to the lathe, two of them would carry abrasive cloth (or something like it) to put a final shine on the inside of the barrel.

I mentioned gun drills earlier, and here’s some information about them. The question often arises: “How do they make that little hole in the gun barrel go down the middle from end to end?” So, here’s an explanation. Since the late 1800s, a solid rod has been made hollow by a gun drill. To make a gun drill bit, a tube is crushed on one side to form a single flute. The tip of the bit was made of hardened steel, or more recently, tungsten carbide, with a hole through its length brazed to the end of the tube. The back end of the bit is made of a thick piece of steel (also with a through-hole) gripped by the drilling machine.

Oil is pumped down through the middle of the drill and into the cutting area under very high pressure, on the order of 1,000 pounds per square inch! The high-pressure oil pushes the material that the drill has cut (the chips) up the flute and out. A gun drilling machine has to have a means of catching the high-pressure oil coming back up the flute. Because the bit is long and relatively flexible, and the tip is asymmetrical, it cannot start its own hole. It must either follow a hole started by another type of drill or be guided at the start in a tight-fitting bushing.

The solid metal tip of the bit is a very tight fit in the hole it’s drilling, which guides the bit as it cuts. The high-pressure oil keeps the bit from being damaged by rubbing on the wall of the hole. Gun drills cut quite rapidly. A rifle barrel might take from 5 to 15 minutes to drill. Gun drills are also used for making other relatively deep holes where straightness, good finish, and a high rate of metal removal are essential. The gun drill in the pictures is .500” (half an inch) in diameter; it could drill to a depth of around 20 inches.

stay up to date

Want more content from the American Precision Museum?

Sign up to receive news straight to your inbox!