Blog

Machine of the Month: The Hubbard Pump

Our Museum has deep connections to this machine.

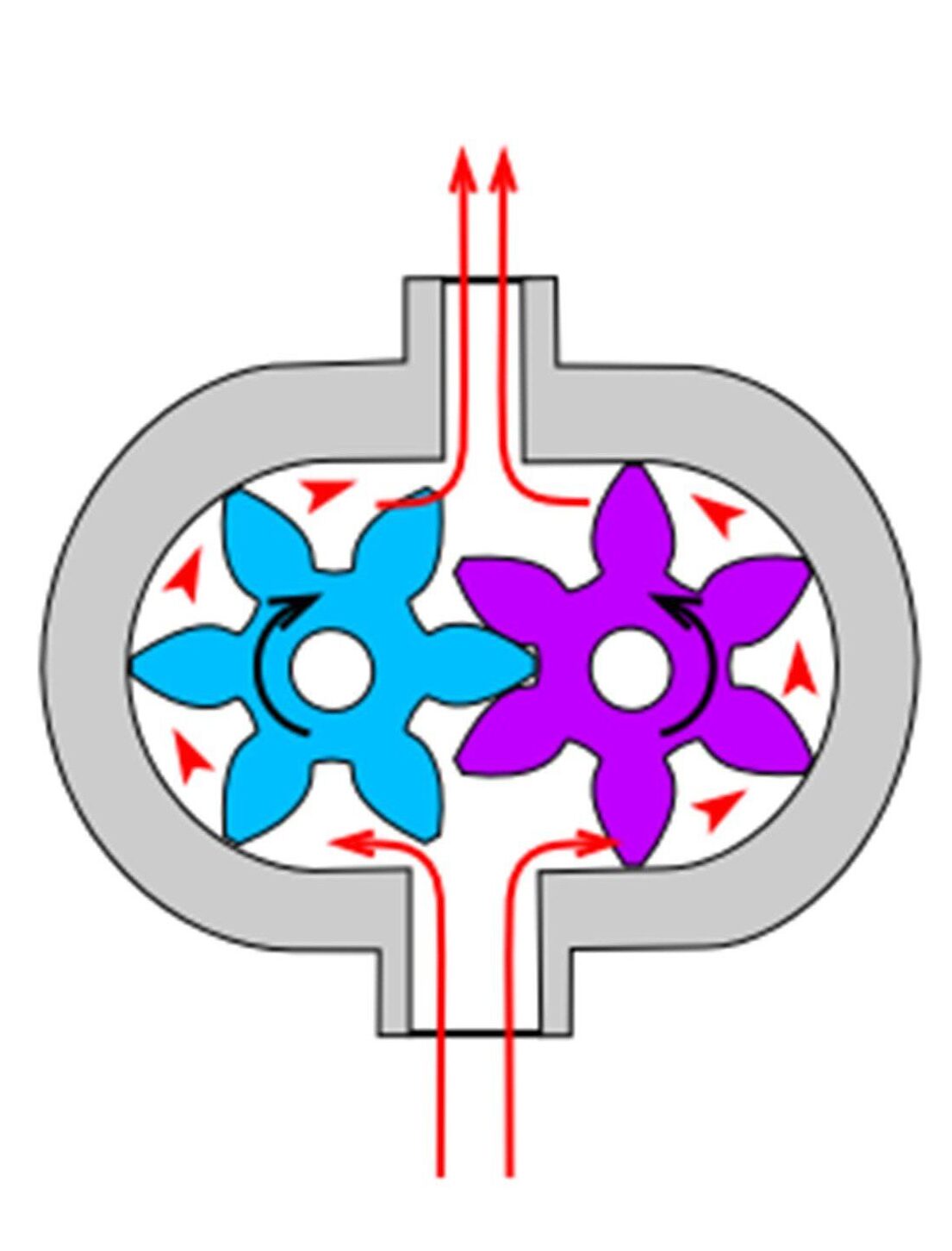

In 1828 Asahel Hubbard patented the first gear pump. After starting to manufacture his pump in Proctorville, a nearby community, Hubbard was able to commence work in 1830 in the State Prison at Windsor using both prisoner and civilian labor. Gear pumps are still common in industrial processes, hydraulic systems, our cars, and oil furnaces. We have to note, though, that the blades of these Hubbard pumps weren’t in the shape of the teeth of a gear. One side of each blade was carefully fitted to mate with the blade on the other impeller.

Making a near-perfect fit along the entire length of the contact area of the blades (about 4 3/8 inches in the case of our pump) was necessary. It was a very unusual feat for the time. It would require careful filing and patient observation of the progress.

The other side of each blade didn’t make contact and was left rough and concave. That concavity created a pocket against the corresponding blade on the other side, which meant that some liquid would pass back down through the middle, where the blades met, which meant loss of efficiency.

We can wonder if they ever changed the shape of the vanes to improve efficiency, but we don’t have much evidence. At the Museum, we have only one assembled pump and one set of impellers. The impellers in the pump appear to be the same shape as the set of impellers alone.

Here’s when things started to relate to our Museum. On September 2, 1835, Nicanor Kendall, who was already working for the pump company, married Laura, daughter of Asahel Hubbard.

Kendall ran the shop at the prison from 1835 to 1842. Then he dropped out of arms making for something over a year. Richard Lawrence, who had been working for Kendall since 1838, was left in charge of the shop. Asahel Hubbard sold the pump business to a shop in Rhode Island, and the firearms work was always Kendall’s thing.

In 1843 Kendall was joined by Lawrence on the north bank of Mill Brook, which formed the company Kendall & Lawrence, primarily a gunsmithing operation. In 1844, they became Robbins, Kendall & Lawrence.

One important thing we must deal with when discussing Kendall is his great-nephew, Guy Hubbard, who died in the 1970s. Guy wrote the “Windsor Industrial History” in 1922. It’s probably the most quoted source on the topic. Unfortunately, he was especially enthusiastic about his relatives, such as his father, George, and Nicanor Kendall. What I mean to say is he told stories that he knew weren’t true.

Guy Hubbard claimed that Kendall’s company made pumps with interchangeable parts. The set of impellers we have that are separate from the pump are certainly not interchangeable. They have a set of witness marks (punches on one blade on the left impeller and punches on two blades on the right one) so that they will be assembled in a way that will make them work.

On the other hand, our assembled pump has no serial number, implying that it’s of the earliest production. The impellers that aren’t in a pump are serial numbered 149.

So, if we use only the evidence on hand, we can’t say if Kendall ever achieved interchangeable parts.

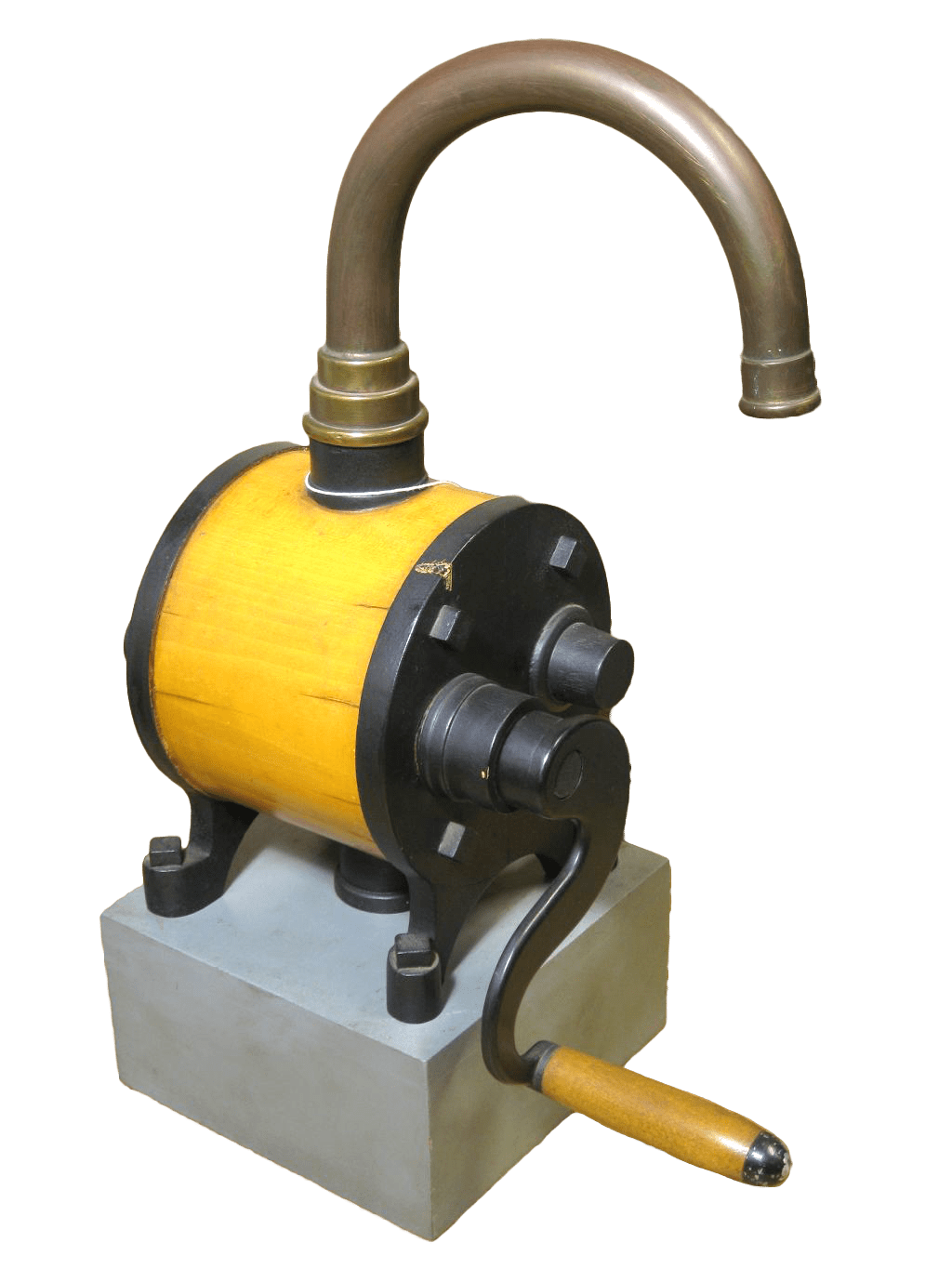

Here’s a little addition, sort of sidelight. We have a full-sized model of a Hubbard pump! It’s mostly wood; the twisty part of the handle is black plastic. The spout appears to be an original one from a genuine Hubbard pump. It’s a tapered, curved tube; I wonder how they did that.

My speculation is that it was made by Guy Hubbard. He was a high school shop teacher and was undoubtedly equipped to build it.

The Museum also has an unused foot valve for a Hubbard pump. The threaded parts are pewter, and the perforated part is galvanized iron. (I’m not sure about the “galvanize” part, but there’s something rust-resistant there.)

To sum up, the Museum has one complete Hubbard pump and one set of impellers. But there are at least three more Hubbard pumps in town. There might also be a Cooper pump. I’ll try to investigate these various machines and report back to you.

stay up to date

Want more content from the American Precision Museum?

Sign up to receive news straight to your inbox!