Blog

Machine of the Month: Daniels Planer

By John Alexander, Collections Technician

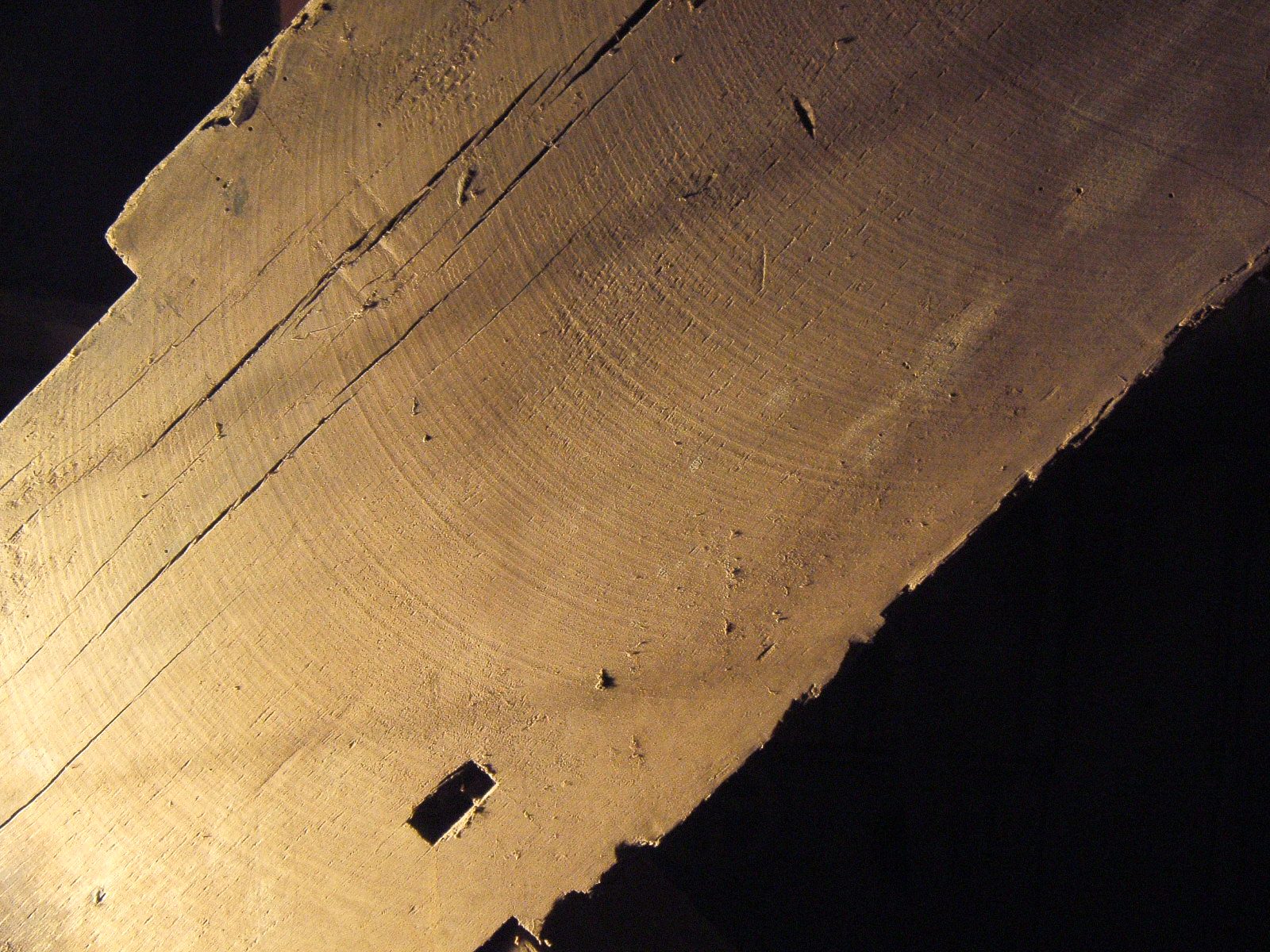

Various pieces of wood in the structure of the Museum’s building show signs of being worked on an unusual type of planing machine. (I’ve found these marks in at least four places, from the basement to the attic.) At first glance, one might think they were formed with a circular saw. But no, a circular saw leaves marks showing that its axel is off to the side of the workpiece. (It has to be because its axel goes all the way through the saw blade.) These pieces of wood have the swirl marks from the cutter teeth centered on the workpiece. The most dramatic example of this unusual, planed wood in the Museum is in the basement, in the diagonal structure that supported the first step in transmitting the power from the water wheel that was there.

By modern standards, these timbers are huge, 11” x 17”. This was the first place that I noticed marks from a Daniels planer.

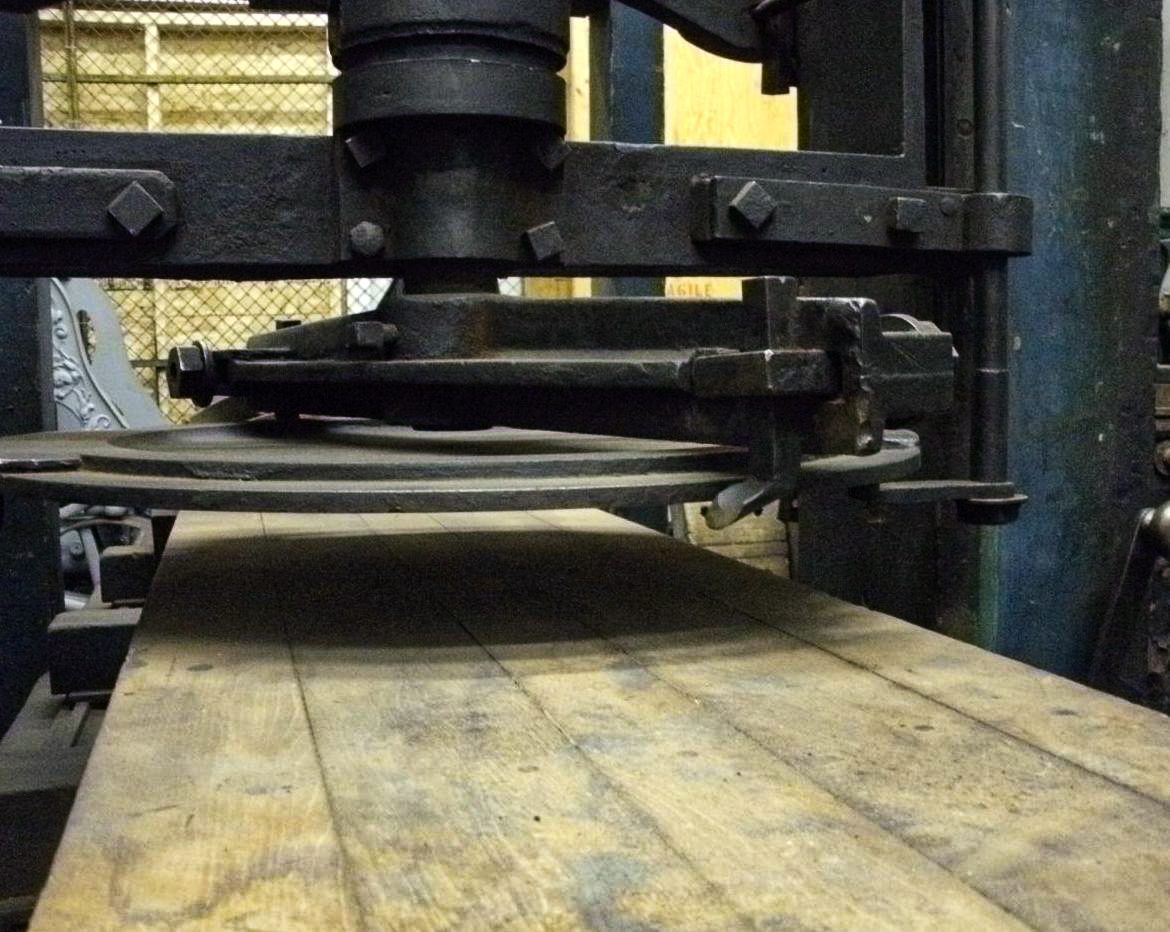

Shortly after, I saw the same tracings on the table of our planer itself. The operator had trued up the surface of the machine by planing it.

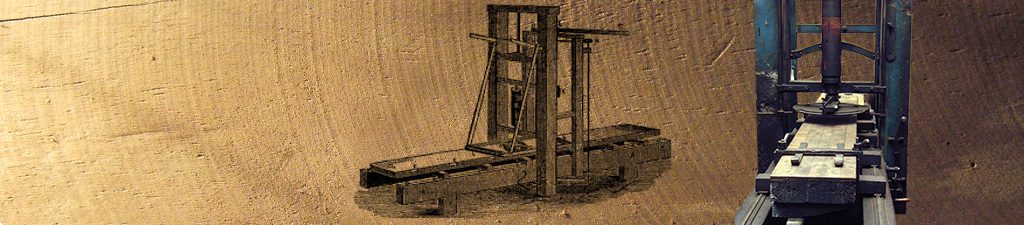

We are fortunate to have a machine that made marks like these. Unfortunately, it’s not on display now. It was patented in 1834.

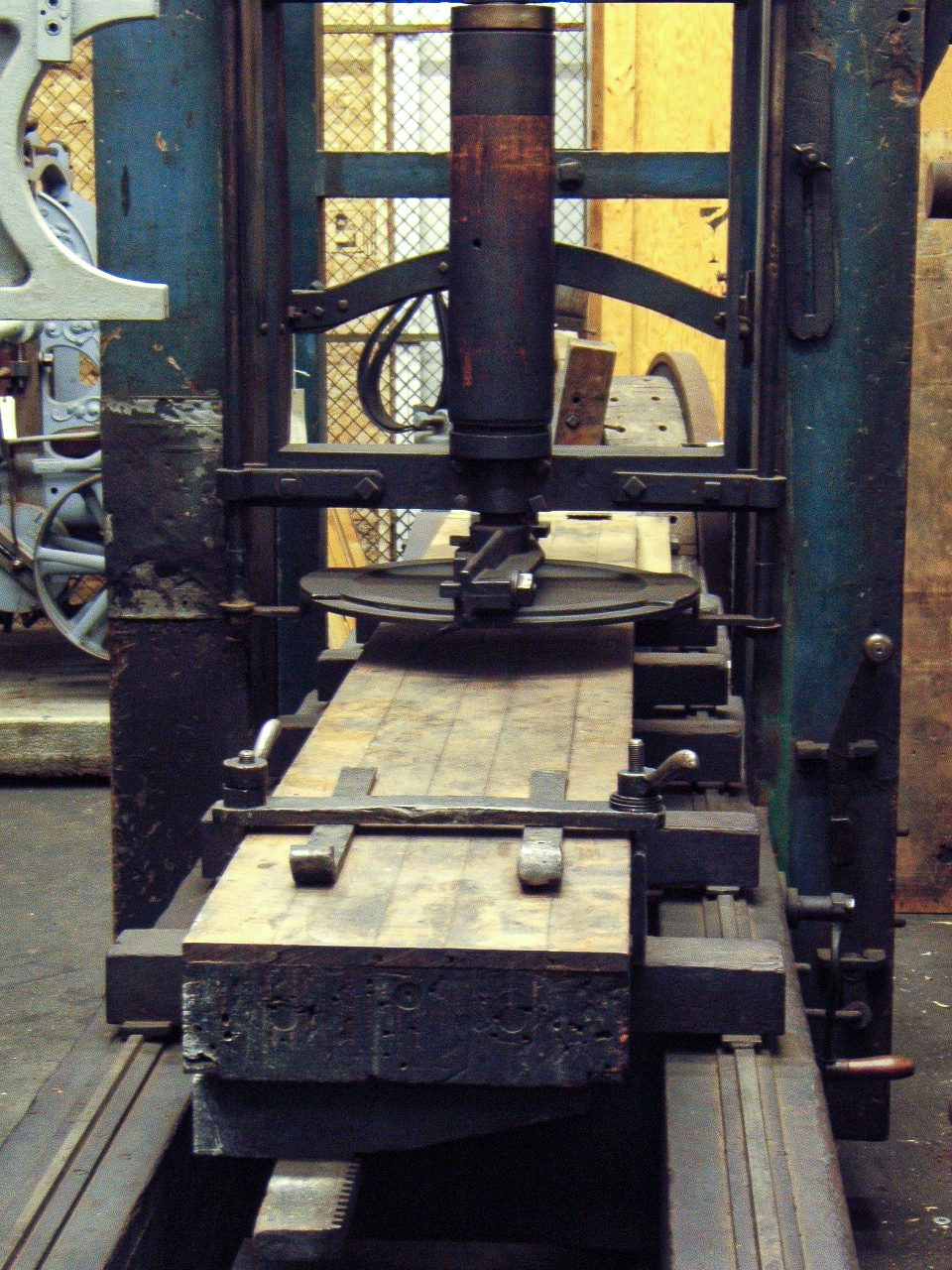

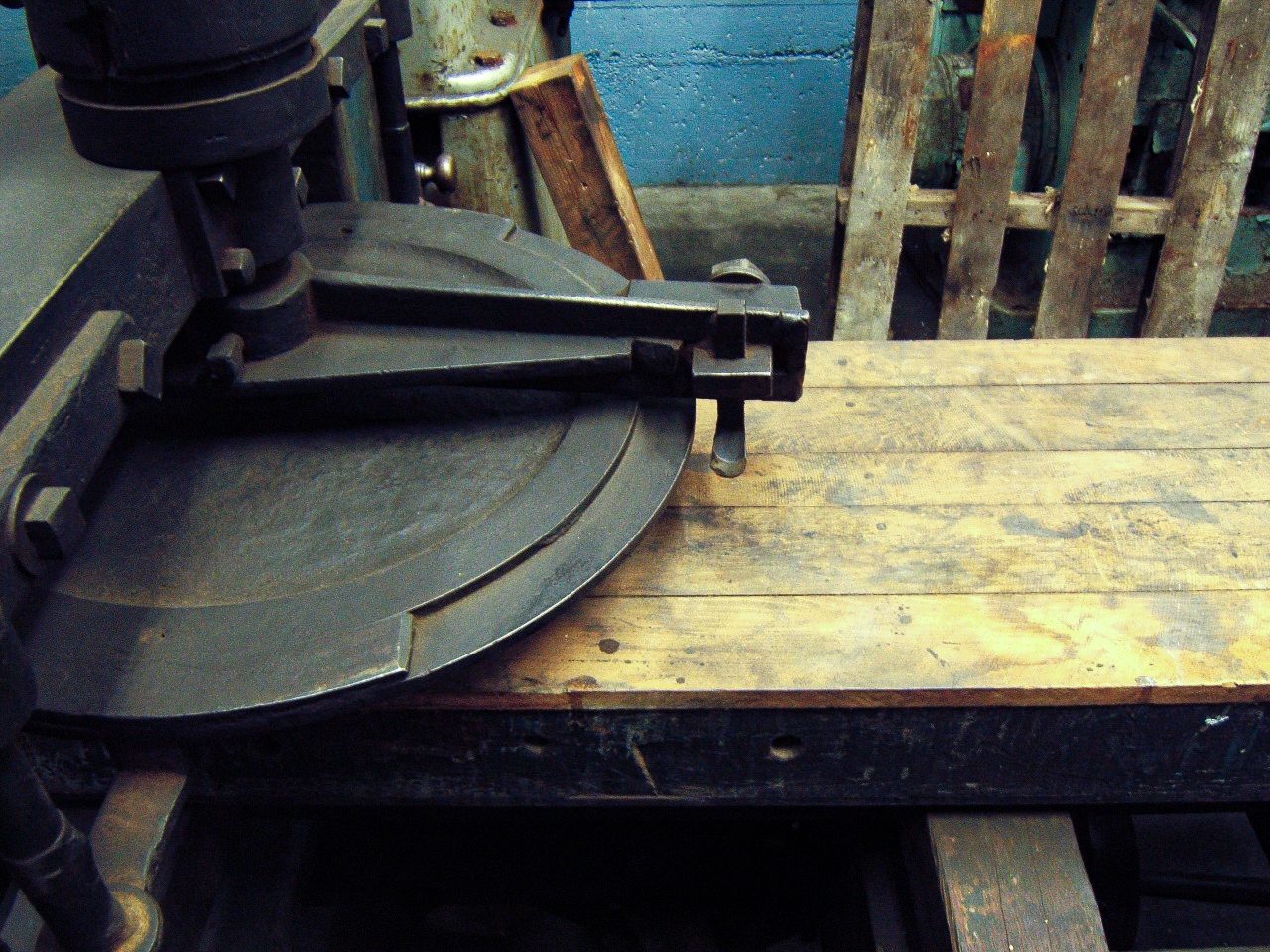

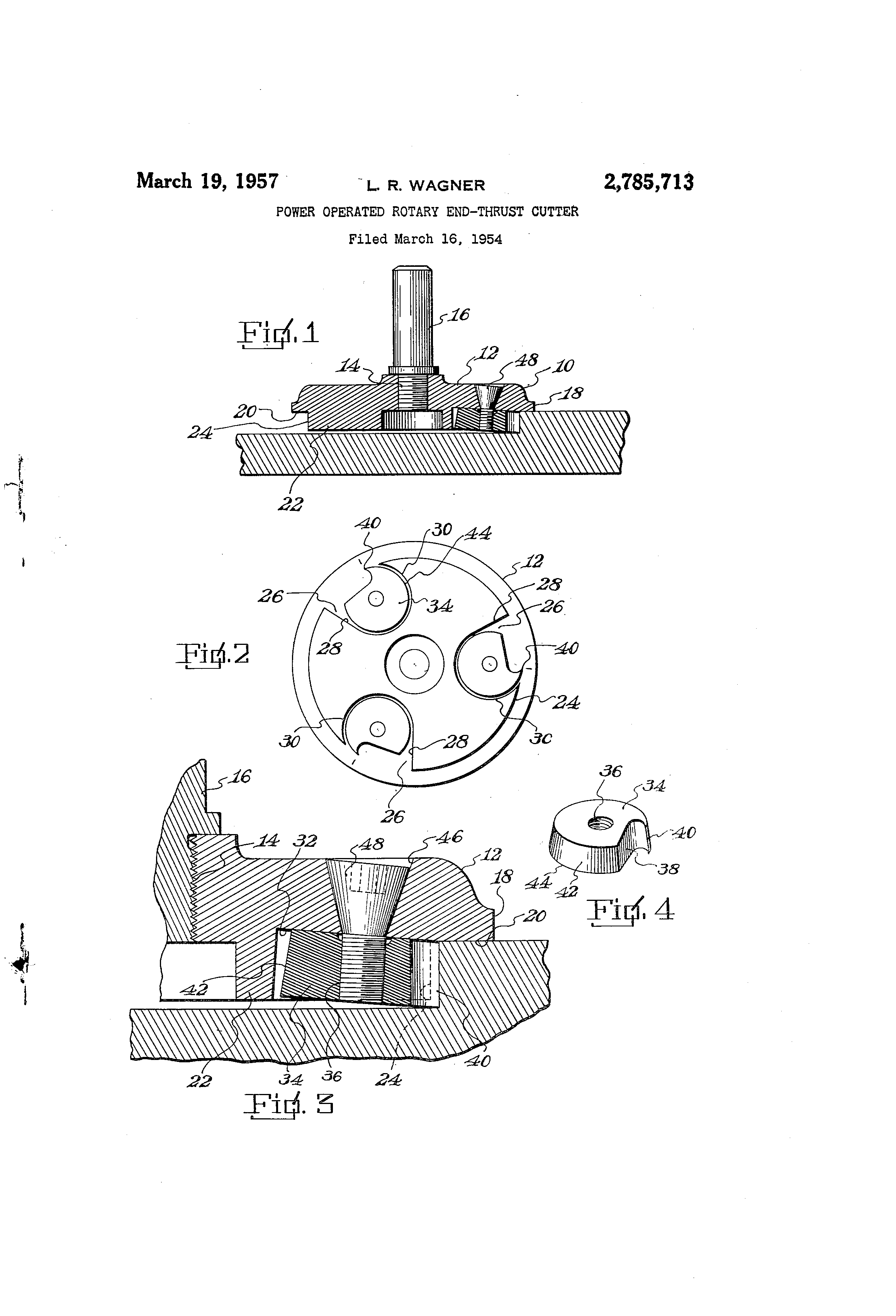

If you know machining, you’ll recognize fly cutting as basically the same procedure. The disc-like structure under the cutter bar doesn’t rotate; it’s apparently a safety feature. The machine has a long sliding table. The work is held to it with toothed dogs. The table slides under the cutter bar. This is where this machine has an advantage over modern planers. Without any special actions, just planing the wood will remove warping from the workpiece. Modern roller-fed machines don’t produce such flat results. The rollers suppress the warp during cutting, and then the workpiece springs back to more or less its original curve. Another advantage is that the cutters can easily be sharpened in any workshop. The roller-fed machines use long knives that must be sharpened precisely on a specialized grinder.

Our machine is large; it can handle a workpiece 18 inches wide and about 10 1/2 feet long. The machine itself is 16 1/2 feet long overall. It’s quite big compared to a modern roller-fed planer of the same capacity and so large that it would be difficult to move from one job site to another. And, of course, it had to be powered by a flat belt, which was a whole other thing! Another problem would be that the work couldn’t flow through as it would in a roller-fed machine. It would take time to dog each piece of wood in place, plane it, and remove it.

There are two pieces of Daniels planed wood as part of the floor in the attic. Between them, there’s some old, thin sheet metal. The metal measures about 54 inches by 16 feet. It probably dates to when the building was a cotton mill (1869-1886.) We don’t know why these things are there or what the metal is. It’s quite soft; a reasonable guess is that it’s zinc.

The Maine State Museum has a Daniels planer that could cut 36 inches wide. It was used in shipbuilding. That idea of eliminating warp in the workpiece must have appealed to shipwrights who needed to fit the ship as tightly as possible to keep water out.

The Slater Mill Museum in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, has a Daniels planer, too. The most distinguishing feature of that machine is its decoration. It has been made fancy by a skilled painter, finished in artificial wood grain painting!

We have a cute little cutter on the same principle as the Daniels planer. It’s called a Safe-T-Planer. It’s designed to be put in the chuck of a drill press. Its width of cut is about 2 3/4”, its maximum depth of cut is about 1/4”. It has an advantage that the original Daniels planers didn’t. It has modern steel teeth, but they have shaped cutters and were no doubt pricey. The U.S. Patent Office approved it in 1957; I remain skeptical as a person interested in the mechanical function of things.

stay up to date

Want more content from the American Precision Museum?

Sign up to receive news straight to your inbox!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact