Blog

Brown & Sharpe Micrometer, 1878

by John Alexander

Our micrometer measuring machine was the brainchild of Oscar Beale, who started life as a Maine farmer, and worked in various mechanical trades. He pursued education, mostly on his own after early grade school, and sought tutoring on difficult material when he was young. When he applied in 1869, Brown & Sharpe almost rejected him, but realized that he had deep knowledge of gearing.

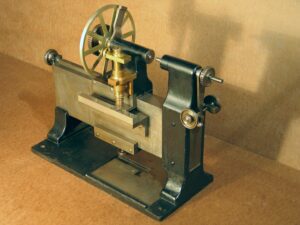

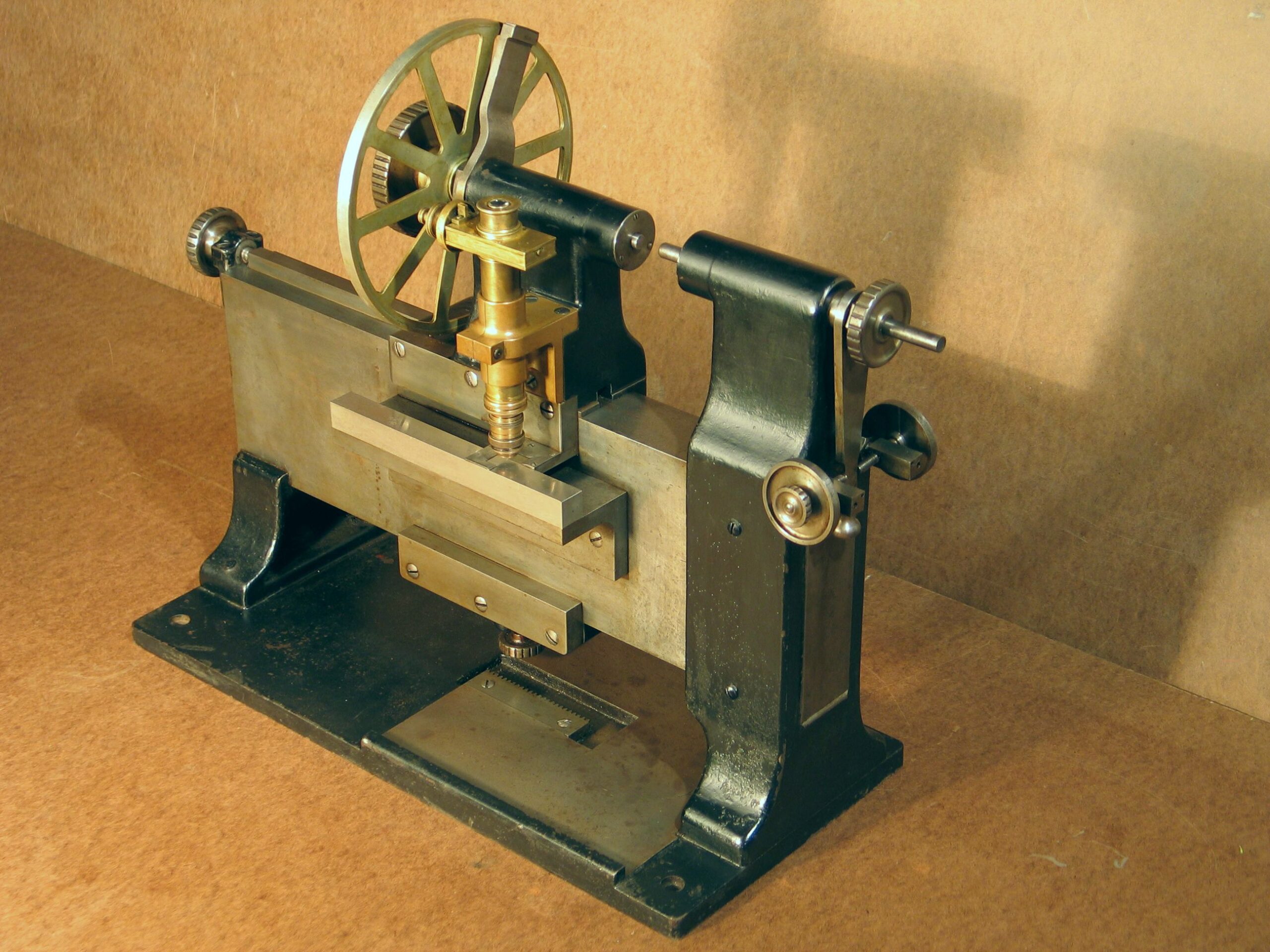

But about the machine itself: It’s very big, 155 pounds, mostly cast iron. It was built in 1878 for use by B&S. It wasn’t for sale. It was extremely precise, readable in hundred-thousandths of an inch. It was tested in the early 1900s and found to be accurate to the millionth of an inch. There were only a very few instruments in the world that were as accurate as this one when it was new.

The question arises, why did they need such an accurate instrument in 1878? Part of the answer must be that they wanted to work pro-actively to anticipate demands for precision in the technological revolution that they were involved in already.

It seems to have started as a realization that they didn’t know the accuracy of tools that they were manufacturing. They undertook detailed collaboration with the Office of Standard Weights and Measures, which has now evolved into the National Institute of Standards and Technology. B&S made standards for length and compared them with the government’s defining standards. When they had completed the project, both parties agreed that the standards were the same.

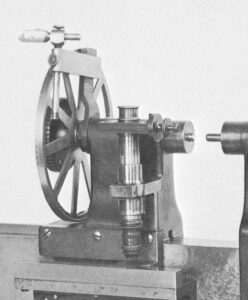

The big wheel is graduated, but it seems that the brass microscope on the front is probably the real heart of the readout.

The bar below it is square and made of something that looks something like German silver, but it does not tarnish in the same way. It has visible graduations dividing inches into twentieths. They aren’t fine enough to be useful to make really precise measurements.

The second of the American Machinist articles mentions a second line of grads along the bar that had become faint over the years. In the last 100 years or so, they have apparently disappeared completely. These were what the microscope looked at with a vernier reticule to make measurements.

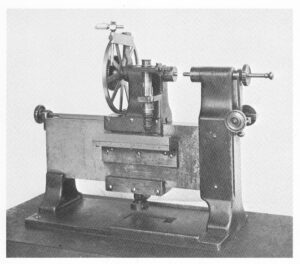

The machine has changed since the Brown & Sharpe photograph from around 1900 that appears in several publications.

Interestingly, it’s now cleaner, or more rust free.

The old photo features a device that I don’t recognize. I assume that it’s to get a sensitive “feel”, to make a consistent pressure on the object being measured. It’s attached to the bent bar the held the vernier over the large wheel.

On the bottom center of the machine in the picture, there’s a nut different from the one that’s there now. The present nut matches the style of similar nuts on the machine.

On the bottom center of the machine in the picture, there’s a nut different from the one that’s there now. The present nut matches the style of similar nuts on the machine.

The second American Machinist article mentions reading the big wheel with a vernier. The piece that can read it now isn’t a vernier, it’s just a single line.

“““““““““““““““““““““`

Sources:

Articles in American Machinist magazine June 27, 1912 and August 6, 1914 help to understand the machine itself and the culture of the men who designed and used it.

Gerald M. Carbone’s book, “Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry” has remarkable details of the company in the machine’s heyday.

stay up to date

Want more content from the American Precision Museum?

Sign up to receive news straight to your inbox!