Blog

Machine of the Month: What is that? Part I

Written by John Alexander, Collections Technician

Sometimes, these artifacts are the most satisfying, sometimes the most frustrating. Our founder, Ed Battison, was a passionate collector but sometimes not the most intensive documenter. The result is that the museum has a relatively large number of objects we don’t understand or at least didn’t previously understand.By “don’t understand,” I mean that some aspects are confusing, and some objects are still completely unidentified.

Soapstone Box

We have a soapstone “box” that’s pretty large (22 ¼” x 7 ½” x 6”) and has large and beautiful female threads cut into the soapstone on each end. We have one matching soapstone plug with male threads (5 ½” long x 4 ½” max. dia.). It has handy spanner flats so that the plug could be gripped and turned, even if it were hot. The hole that passes through the length of the box is about the same as the major diameter of the plug’s threads.

There’s also a hole in the side of the box. That hole was originally round and about 1 1/8” dia., but it has blown out and is now more-or-less elliptical. There are signs that there has been a fire inside the box. That isn’t surprising since soapstone has been, and still is, used in many places that have high heat.

The plug has a hole through it (parallel to the central hole in the box). Part of the hole is lined with a short metal sleeve, possibly to protect the soft soapstone from abrasion from the turning of a shaft that might have passed through the length of the box.

We don’t know anything else about this object.

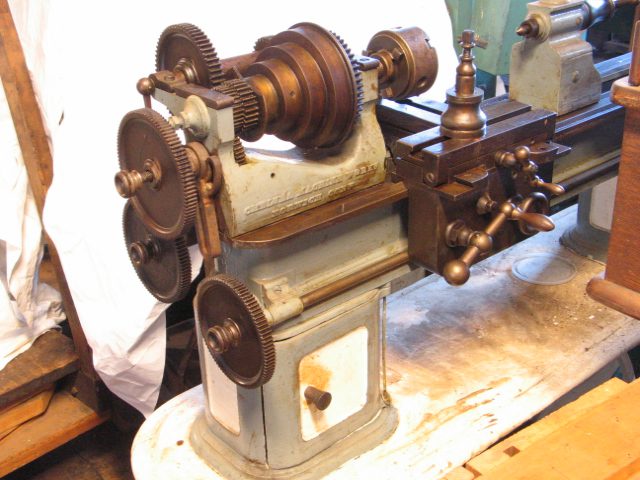

Brass Guards

We have two brass guards that weren’t associated with a particular machine for many years. Then a video surfaced that had been taken in 1987 by trustee Camiel Thorrez. The subject was a tour of the exhibit floor narrated by Ed Battison. In the video, the brass guards were on “our” Blanchard lathe that’s designed to shape the butt of rifle stocks.

I put “our” in those quotation marks because that lathe is on loan to us. The machine was made by Ames Manufacturing Company of Chicopee, Mass., and sold to the British for their Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield. It worked there for about 100 years, then was given to the U.S. Park Service, which loaned it to us.

Interestingly, I recently saw the following picture on the Harpers Ferry Armory Museum website. Their lathe has guards that were undoubtedly made by the same person.

I assume that that lathe also worked long and hard in Britain.

One thing about the guards: they are to protect the machine’s gears from getting clogged with wood chips. If the machine were run with stuffed gears, something in the machine would probably break. They clearly didn’t have the same concerns for their worker’s fingers; neither our machine nor the one at Harpers Ferry has belt guards.

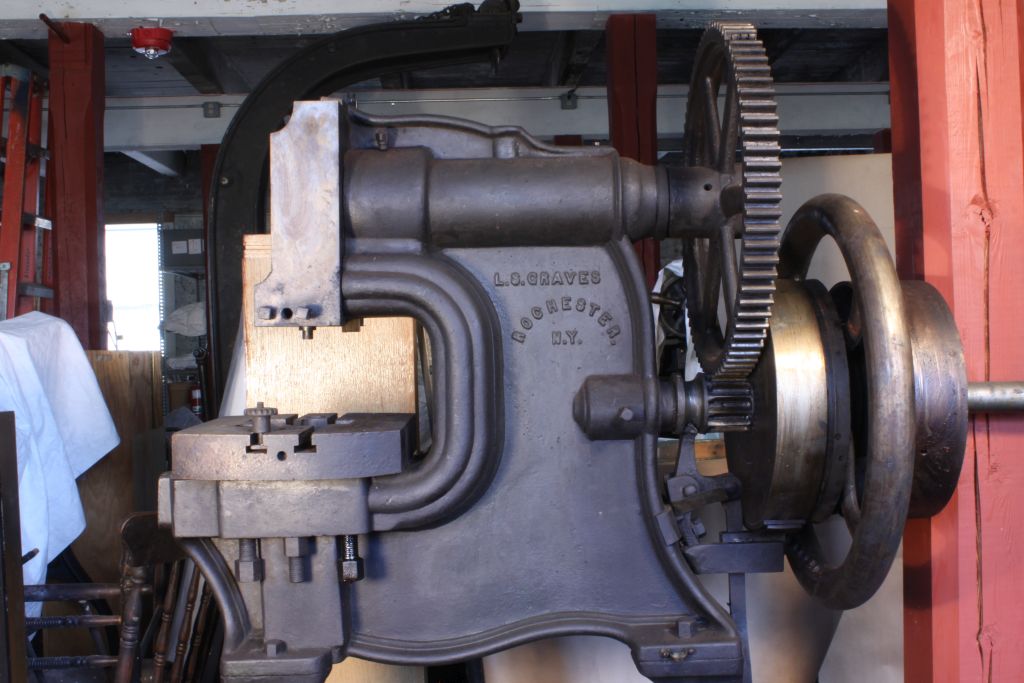

Press

We have a mechanical press that I thought had two pulleys that could be driven by leather flat belts. After many years of believing that, I realized one of these cylinders was a combination brake drum and clutch.

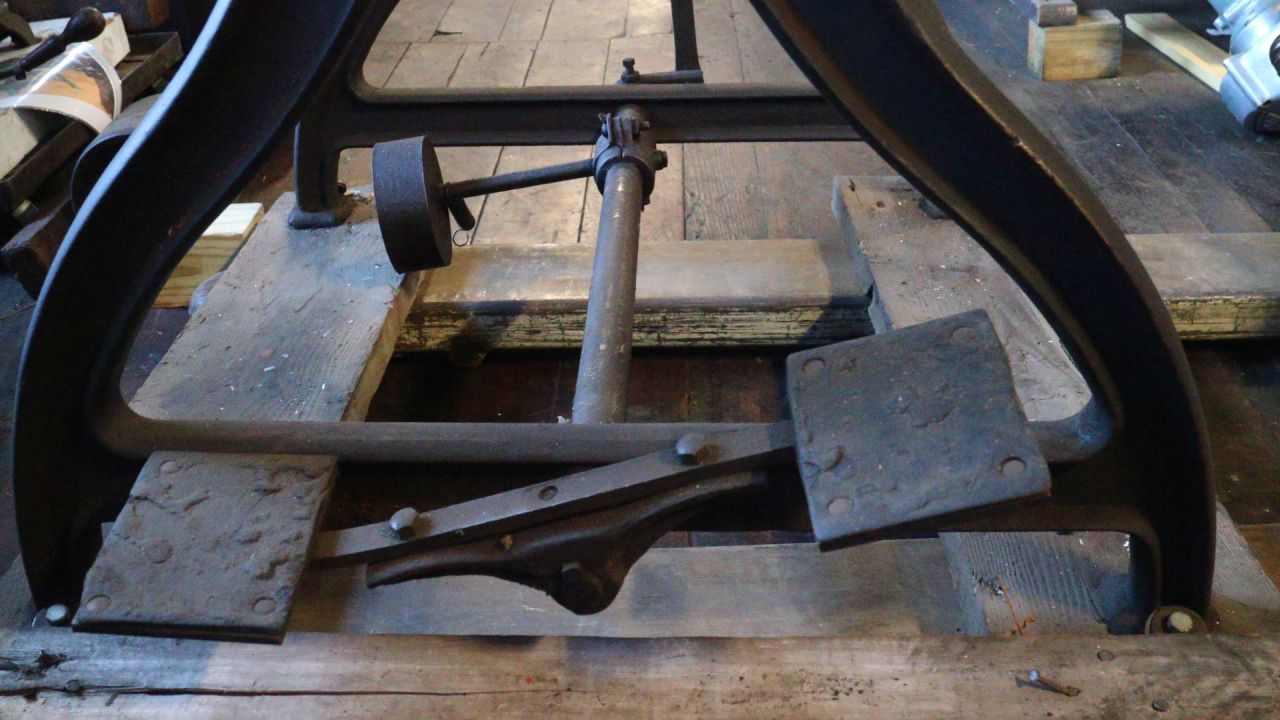

The actual pulley (the cylinder on the right in the picture) would spin continuously. To operate it, the operator would step on a pedal under the work table. This would lift the brake pad out of contact with the outer surface of the brake drum, allowing it to spin. That same pedal pressure would push a conical friction surface into the inside of the same drum. This connected the press’s working mechanism to the pulley, the machine’s power source. The press cycled until the operator stopped pressing the pedal on the right side. Then, the clutch was released, and the brake automatically came on. That disc jutting out to the left is a weight that would disconnect the drive system. There’s also a second pedal on the left that seems to be for stopping in case the mechanism gets stuck in the “on” position.

Among the interesting features of this machine, the large gear that is part of this drive mechanism was broken long ago. It was brazed back together so well that you might not notice it. Well, enough that the relatively coarse gearing probably didn’t object at all. But one gear tooth was apparently wrecked when the gear was broken. Where the tooth had been, the repairman drilled a line of 3 holes very close to each other. He put pins in the holes. They are held tightly by some means, by friction, by being threaded, or by brazing. When they were secure, the repairman filed the new line of pins to approximate the profile of the other teeth.

APM has at least one other place where this kind of tooth repair is used. At the Hagley Museum in Delaware, some gears (not installed on a machine) are on display that look like they ran into a thick-quilled porcupine. They have many restored teeth.

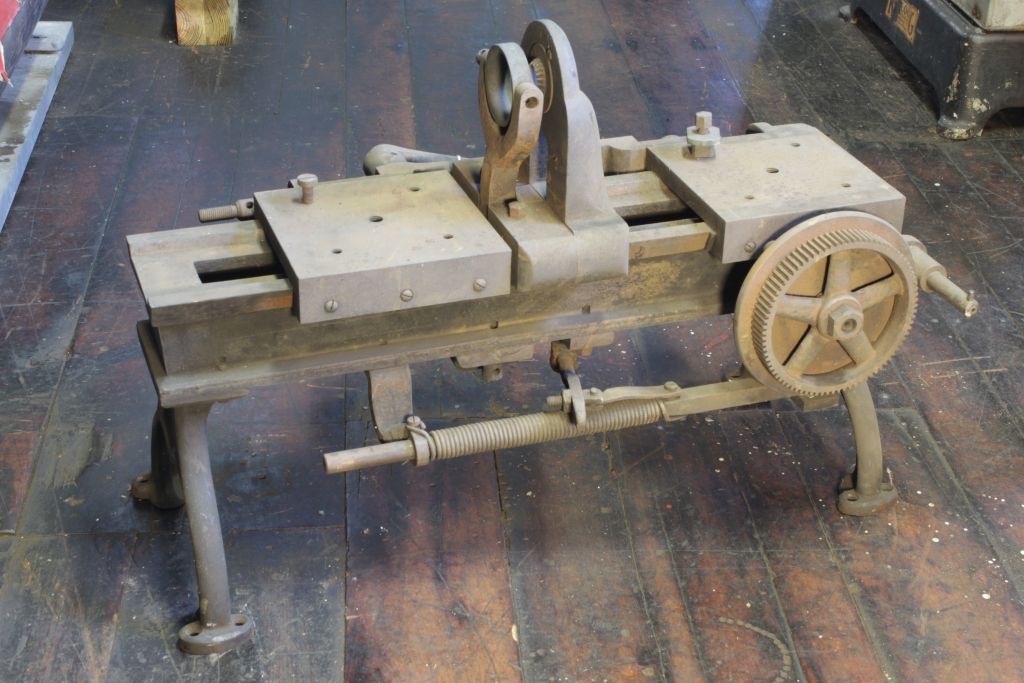

Rattan Stripper

We have a machine that would puzzle almost anyone who might want to identify it. Much of the original machine is gone. It’s for stripping rattan (also spelled “ratan”). Ed Battison got it because he wanted some parts from it, not for its historical value. If he hadn’t mentioned it, we would have no idea what it was.

That illustrates our problem in dealing with these “unknown” devices. Some could be unique wonders of old technology or be best thought of as scrap.

Chelsea Machine Works Lathe

One unique thing complicates understanding these various objects. Ed Battison sometimes disassembled machines and separated the parts.

He said that this was to discourage people from stealing them, and that was probably entirely true. However, it seems likely to me that what was really going on sometimes was that he was guarding his intellectual turf, or occasionally, he was keeping knowledge to himself. Anyway, it hasn’t made sorting it all out any easier.

None of these devices are on display now, but if you go on a Behind the Scenes tour, you can see all of them except the Chelsea lathe.

If you are interested, be sure to call ahead to arrange a tour.

stay up to date

Want more content from the American Precision Museum?

Sign up to receive news straight to your inbox!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact