Blog

Machine of the Month: Brown & Sharpe Universal Mill

Written by John Alexander, Collections Technician • jalexander@americanprecision.org

My choice of this machine was confirmed right away. I looked in a box of books sitting next to my desk and immediately found a book with my target machine on the cover!

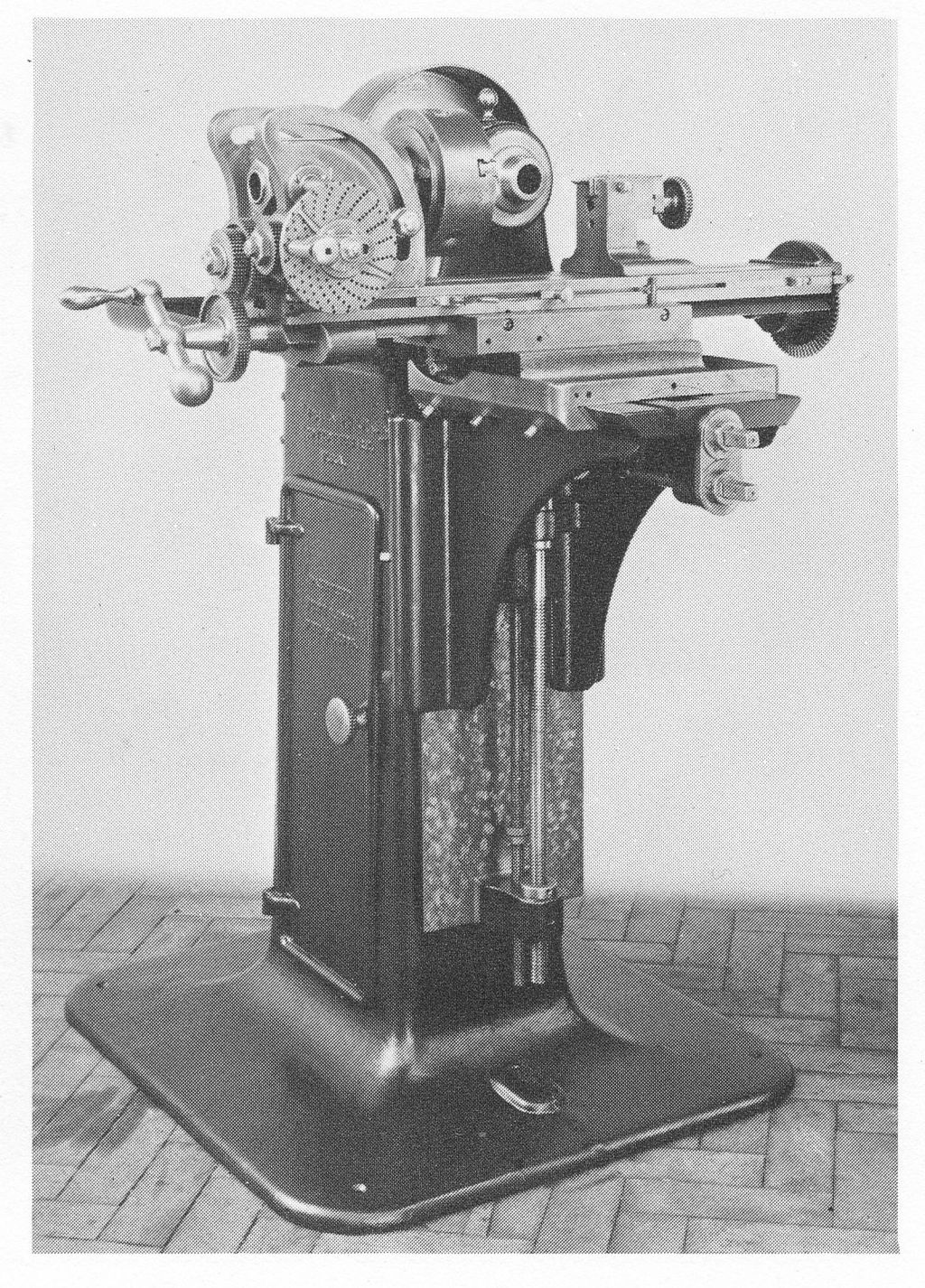

So what makes this a “universal” machine? It has two features built into it that a common horizontal mill would not have. The table can pivot a substantial amount in a horizontal arc, and it can be locked there. This is good for cutting tapers. In this photo from Foundations of Mechanical Accuracy (available in the APM Museum store), you can see parts our machine doesn’t have anymore. These are gears and an axle on the left and the tailstock on the right.

Part of the package is that elaborate geared device on the left end of the table. It’s an index head. It can do various things, but the way it would have served Howe was that it was driven by the leather belt from overhead to a pulley, a second pulley, through a shaft joined by universal joints, more gears, the drive screw that moves the table left-and-right, then several more gears, some of which are inside the indexing head. This motion turned the workpiece and moved the table left or right. Since the milling cutter wouldn’t change its position, these two motions of the workpiece and table would make a spiral cut into the cylindrical surface of the workpiece. Just what’s needed to make the form of a twist drill.

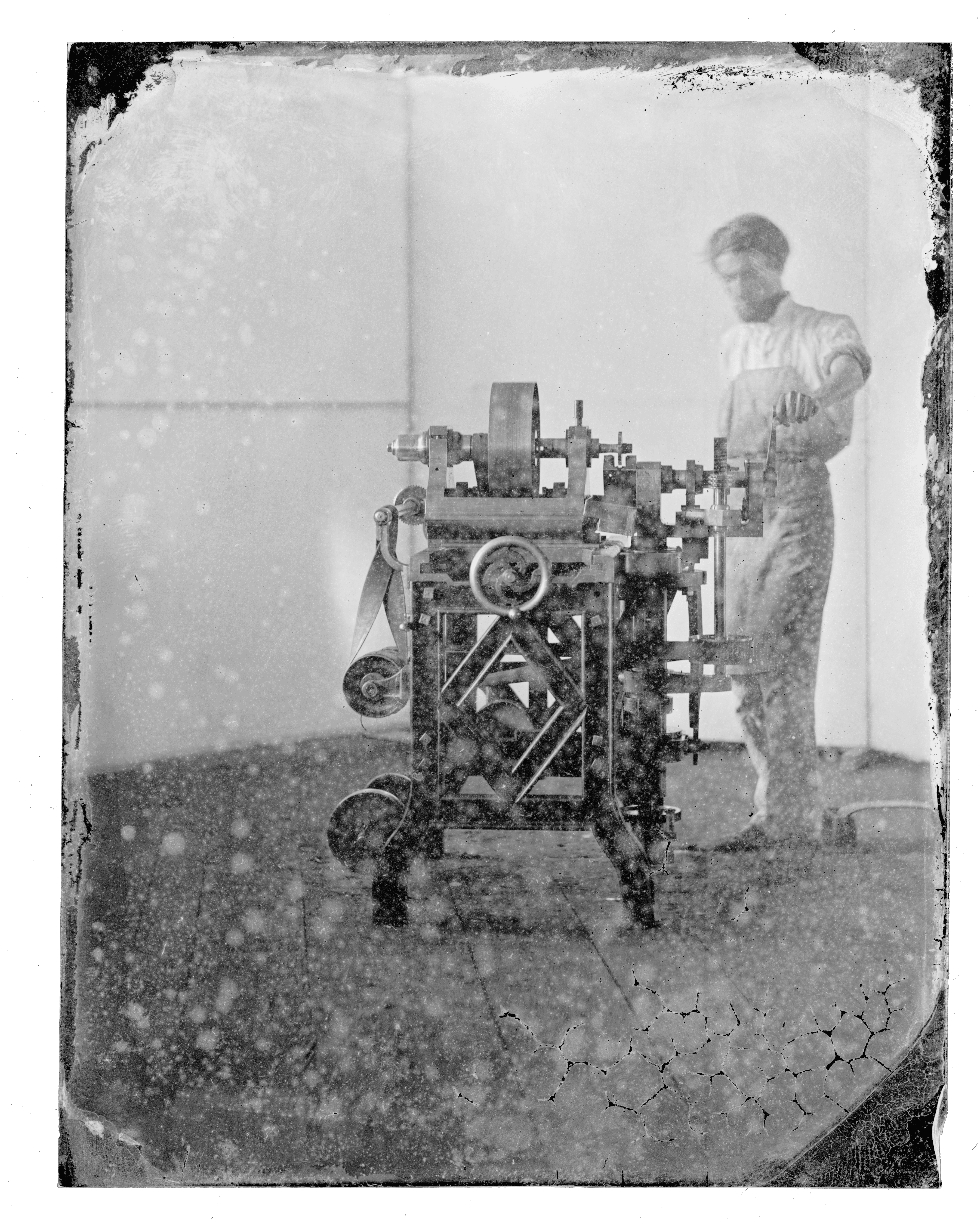

The story goes that Fredrick Howe, working at Providence Tool Company, needed twist drills, so he asked Joseph Brown of Brown & Sharpe (both companies being in Providence, Rhode Island) to design and build a milling machine that could cut the helical flutes wrapping around the drills. The first machine tool that B&S had made for sale was a turret lathe that Howe had asked Brown for to make percussion cap nipples. The nipples also needed to have a hole drilled through them, and that was best done with twist drills. The nipple is a small device threaded on one end to attach to a muzzle-loading gun and has a smooth taper on the other end on which the cap is seated.

The hole through the nipple carries the fire from the percussion cap’s explosion to ignite the gunpowder charge in the gun’s barrel.

Making a small diameter drill bit to drill the hole would not have been easy with the equipment of the day. The twist drills were made by hand by carefully filing the two spiral grooves (flutes) for lubricant and chips to move in.

This was the time of the Civil War, and there was lots of pressure to achieve challenging production goals. If production could be increased, it would need to be done.

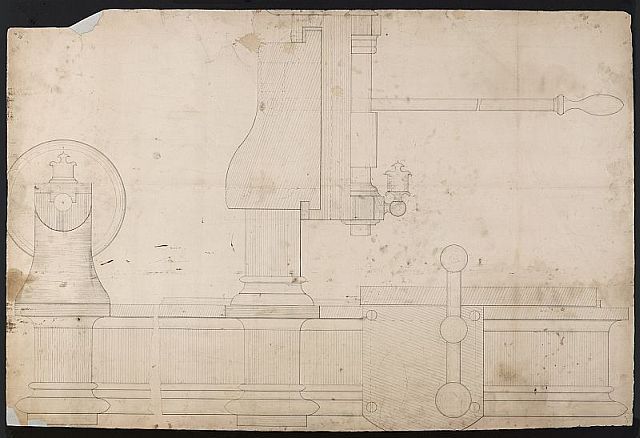

Fredrick Howe was brilliant at machine design himself. He created a number of ground-breaking machines in his years in Windsor, VT, with Robbins & Lawrence. American Precision Museum’s collection includes a profile milling machine, the horizontal milling machine he had designed, and a pistol rifling machine.

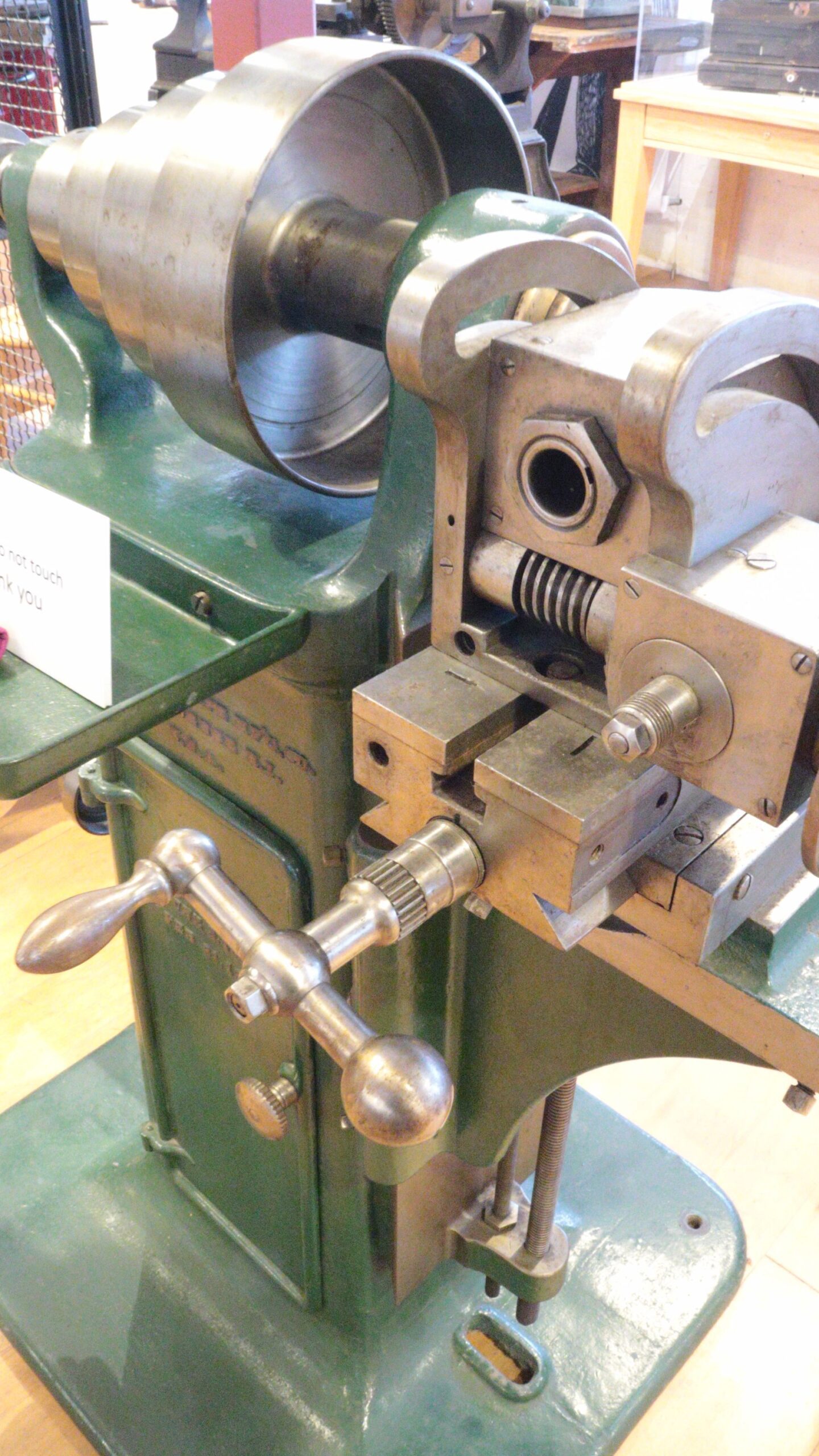

We also have a Howe-designed mill that would most likely qualify as a “universal” milling machine. It was probably designed for use in a tool room. It has all sorts of capabilities, perhaps more different ones than the B&S machine, but it’s clumsy and rickety compared to the Brown & Sharpe machine, not nearly as practical for most work. And it couldn’t cut spirals.

These four machines were very influential, and they are all displayed on APM’s exhibit floor now. (As is our Browne & Sharpe universal mill.) Howe was such a remarkable machine designer himself that I suspect that he did a significant bit of the design work on the Brown & Sharpe universal mill. After all, the universal mill was only the second machine tool that Brown & Sharpe had made for sale outside the company. Many of the machines that Howe had designed at R&L had been sold and were working for satisfied customers.

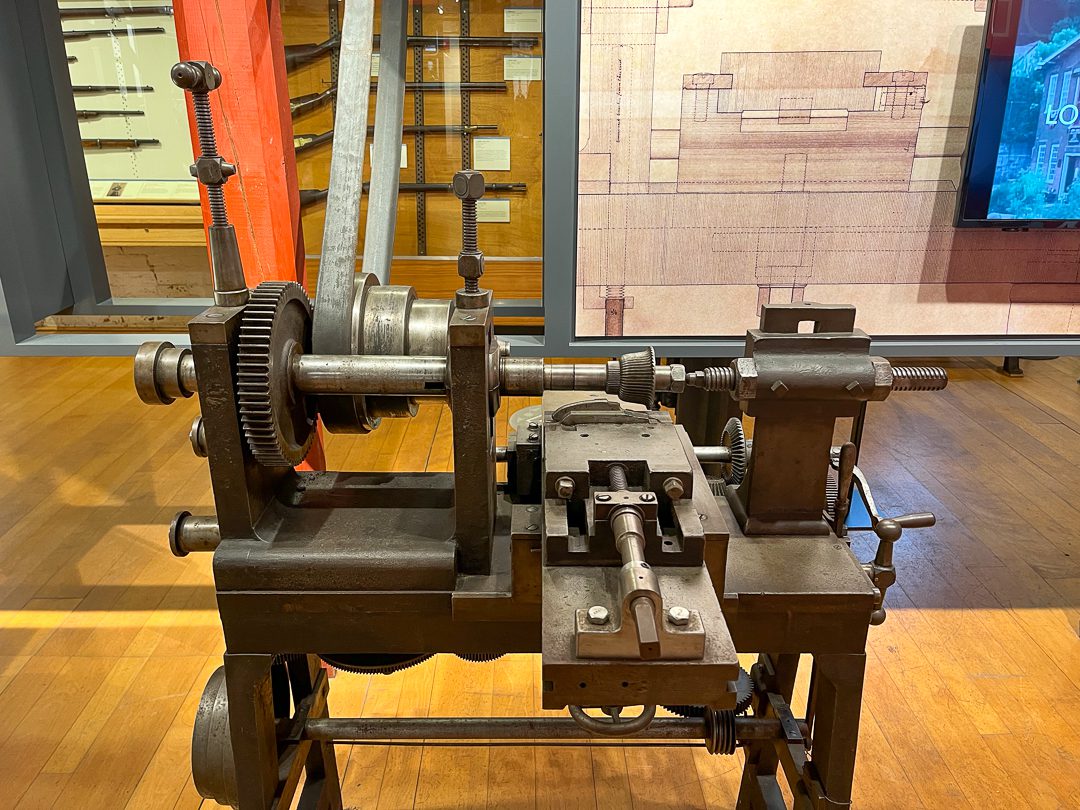

Please don’t think that I believe that Joseph Brown was not a remarkable designer himself. APM has the original “linear dividing engine” that Brown designed in 1850 to cut the graduations on rulers and on verniers. It’s a fabulous machine, amazingly accurate, with various subtle mechanical workings. The first Brown & Sharpe universal mill was delivered to Providence Tool on March 14, 1862. It was soon praised as being a major breakthrough. In a testimonial dated May 10, 1865 (the Civil War ended May 26, 1865) F.W. Howe wrote about the machine: “I take great pleasure in recommending your celebrated universal milling machines which are all that their name indicates and are exceedingly useful for making machine tools of every description. Those we have had in use for the past three years are considered two of the most useful and profitable machines for making tools that we have in our armory.” It’s interesting that Howe doesn’t even hint at drill bits at all in that testimonial.

Please don’t think that I believe that Joseph Brown was not a remarkable designer himself. APM has the original “linear dividing engine” that Brown designed in 1850 to cut the graduations on rulers and on verniers. It’s a fabulous machine, amazingly accurate, with various subtle mechanical workings. The first Brown & Sharpe universal mill was delivered to Providence Tool on March 14, 1862. It was soon praised as being a major breakthrough. In a testimonial dated May 10, 1865 (the Civil War ended May 26, 1865) F.W. Howe wrote about the machine: “I take great pleasure in recommending your celebrated universal milling machines which are all that their name indicates and are exceedingly useful for making machine tools of every description. Those we have had in use for the past three years are considered two of the most useful and profitable machines for making tools that we have in our armory.” It’s interesting that Howe doesn’t even hint at drill bits at all in that testimonial.

In an article about progress in machine tools in American Machinist Magazine in the early 1900s, we also have, “Probably no other single machine has exerted so great an influence upon the character of machine-shop and tool-room work as has the universal milling machine, and if it were to be banished from our shop their efficiency would be greatly reduced. It is the machine tool, which above all others, has intelligence and brains worked into it, and no other is capable of doing so wide a variety of work. It will, within limits, do all the work of the driller, planer, and lathe, besides doing a wide variety of work peculiar to itself and which it is impracticable or impossible to do on any of the others named.” These responses are remarkably similar to those which greeted the Bridgeport milling machine, which came out 76 years later.

The part that carries the work-holding table is the vertical slide called the “knee.” It was introduced on the universal mill and remains an essential component of many modern milling machines, including the Bridgeport. Later on, Fredrick Howe was employed by B&S and rose to become president of the company. In his time with them, he designed a number of machines. We have one of those that is credited to him, a Number 12 horizontal milling machine. It’s larger and much stronger than that original universal, but it’s not nearly so versatile. It is in storage, not on display. To see the machines that aren’t on display, please book a Behind the Scenes Tour of our collection.

stay up to date

Want more content from the American Precision Museum?

Sign up to receive news straight to your inbox!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact