Blog

Machine of the Month: Photostat Machine

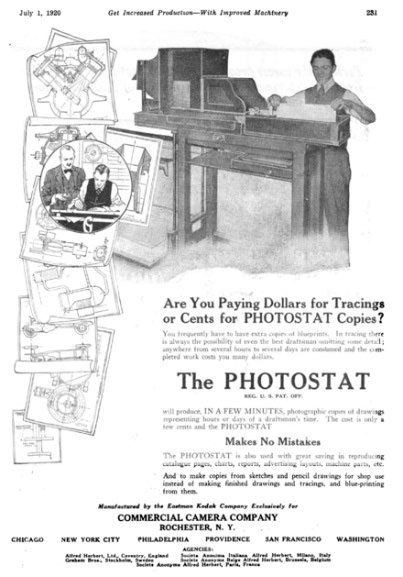

The Photostat brand machine, differing in operation from its competitor, Rectigraph but with the same purpose of the photographic copying of documents, was invented in Kansas City by Oscar T. Gregory in 1907. In 1911, the Commercial Camera Company of Providence, Rhode Island, was formed. By 1912, Photostat brand machines were in use, as evidenced by a record of one at the New York Public Library. By 1913, advertisements described the Commercial Camera Company as headquartered in Rochester and with a licensing and manufacturing relationship with Eastman Kodak. The Commercial Camera Company became the Photostat Corporation around 1921, for “Commercial Camera Company” is described as a former name of Photostat Corporation in a 1922 issue of Patent and Trade Mark Review. For at least 40 years, the brand was widespread enough that its name was genericized by the public.

Photostat machines consisted of a large camera that photographed documents or papers and exposed an image directly onto rolls of sensitized photographic paper that were about 350 feet (110 m) long. A prism was placed in front of the lens to reverse the image. After a 10-second exposure, the paper was directed to developing and fixing baths, then either air- or machine-dried. Since the print was directly exposed without using an intermediate film, the result was a negative print. A typical typewritten document would appear on the photostat print with a black background and white letters. Thanks to the prism, the text would remain legible. Producing photostats took about two minutes in total. The result could, in turn, be photostated again to make any number of positive prints.

The photographic prints produced by such machines are commonly referred to as “photostats” or “photostatic copies.” The verbs “photostat,” “photostatted,” and “photostatting” refer to making copies on such a machine in the same way that the trademarked name “Xerox” was later used to refer to any copy made using electrostatic photocopying. People who operated these machines were known as photostat operators.

Photostat machines consisted of a large camera that photographed documents or papers and exposed an image directly onto rolls of sensitized photographic paper that were about 350 feet (110 m) long. A prism was placed in front of the lens to reverse the image. After a 10-second exposure, the paper was directed to developing and fixing baths, then either air- or machine-dried. Since the print was directly exposed without using an intermediate film, the result was a negative print. A typical typewritten document would appear on the photostat print with a black background and white letters. Thanks to the prism, the text would remain legible. Producing photostats took about two minutes in total. The result could, in turn, be photostated again to make any number of positive prints.

The photographic prints produced by such machines are commonly referred to as “photostats” or “photostatic copies.” The verbs “photostat,” “photostatted,” and “photostatting” refer to making copies on such a machine in the same way that the trademarked name “Xerox” was later used to refer to any copy made utilizing electrostatic photocopying. People who operated these machines were known as photostat operators.

stay up to date

Want more content from the American Precision Museum?

Sign up to receive news straight to your inbox!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact