Blog

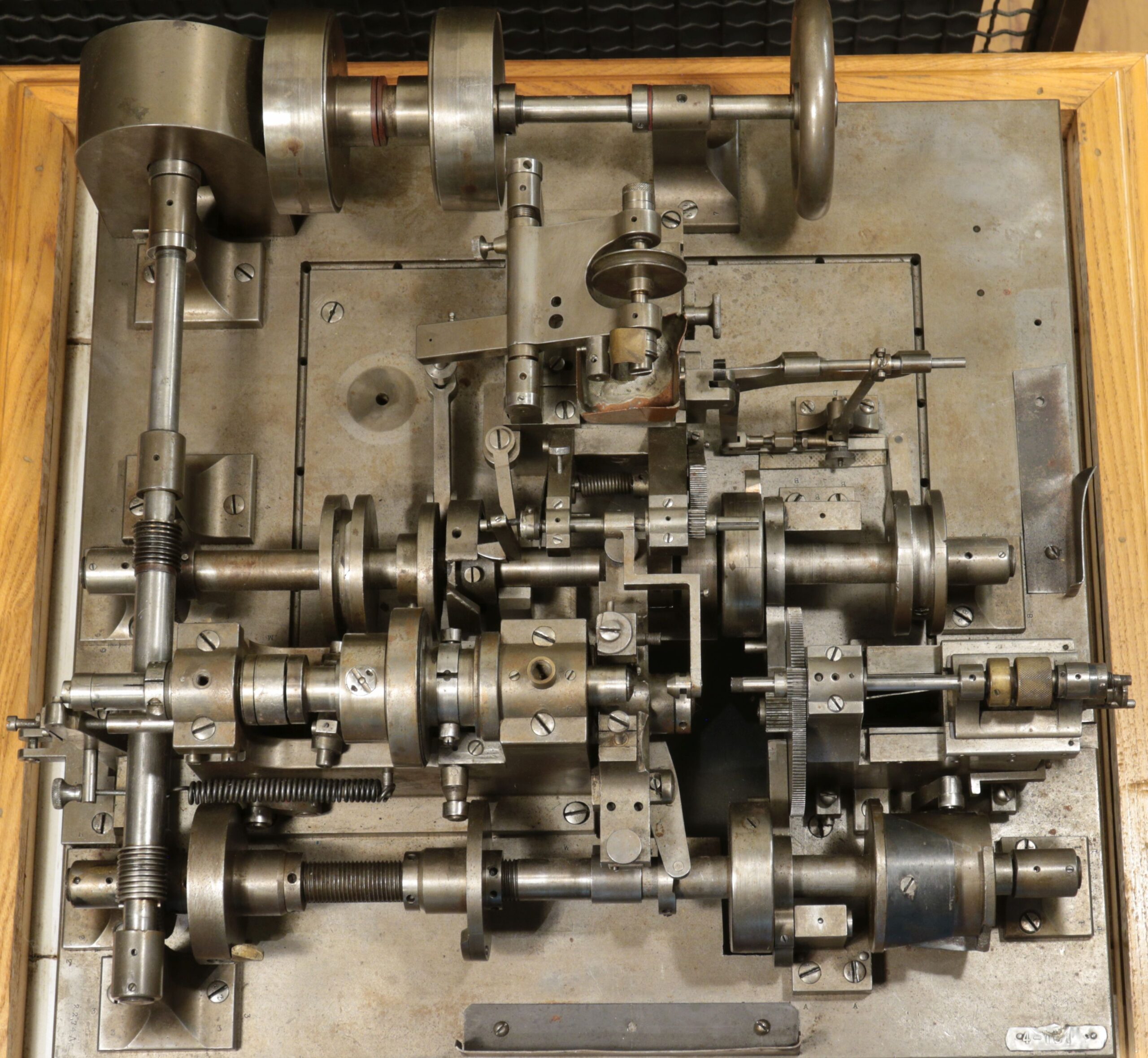

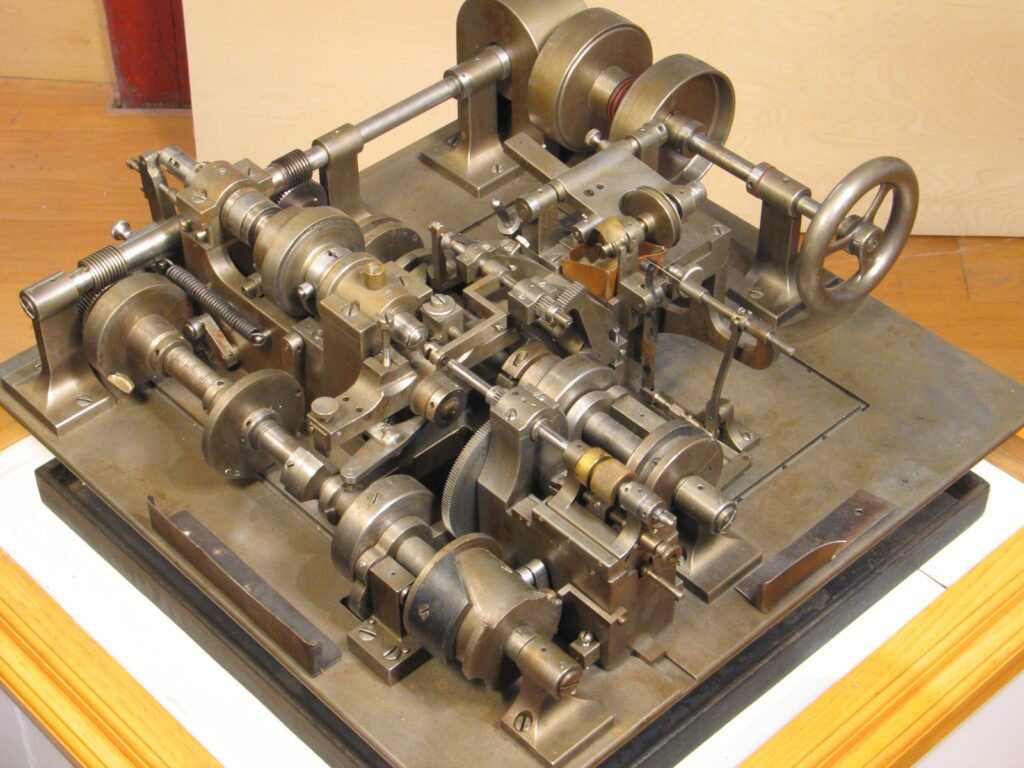

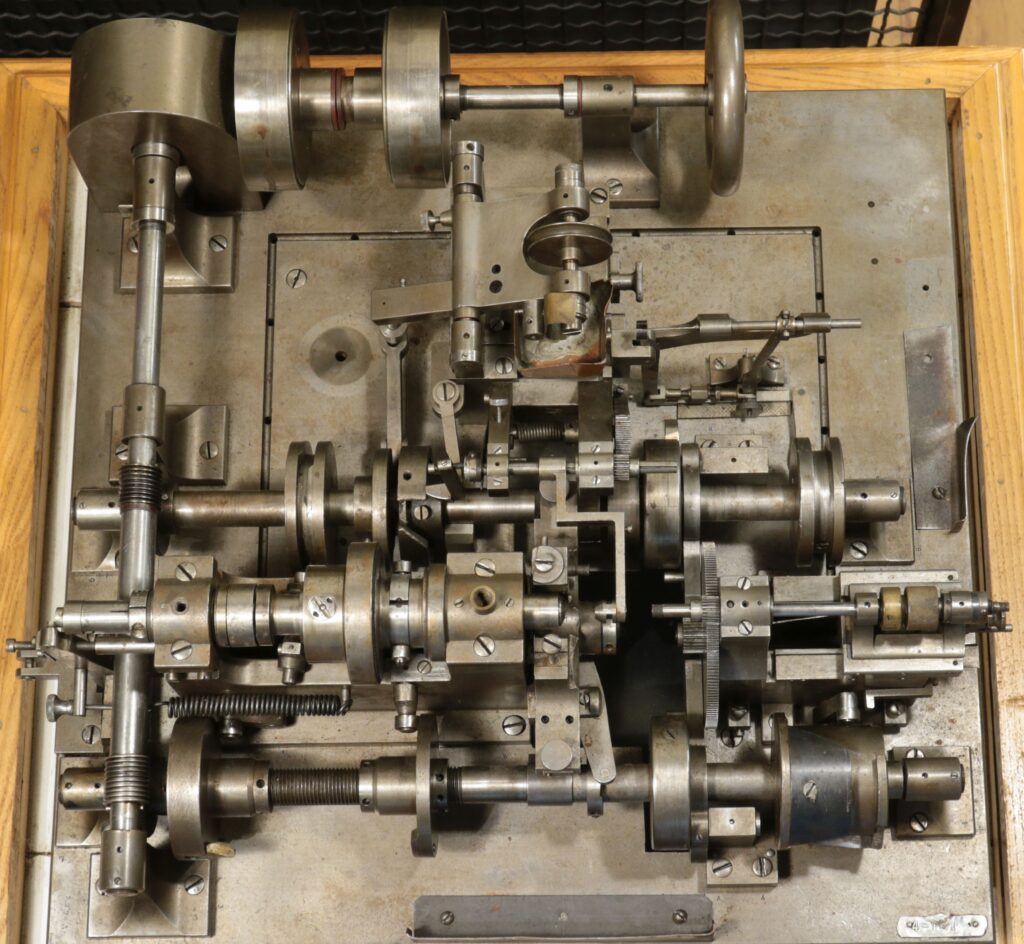

Automatic Lathe, 1871

One of the notable mechanical achievements of the 19th century, Charles Vander Woerd’s watch screw-making machine is something that still impresses viewers. Mainly, it’s the subtle design, but it’s also how wonderfully it was realized.

Vander Woerd (1821 – 1888), a supervisor at American Watch company of Waltham, Massachusetts, was able to create this sophisticated device without standing on the shoulders of preceding inventors of automatic lathes. We know this because his was almost certainly the first. He created it in 1871. Rather than patent it the American Watch Company, chose to keep it proprietary, that is to say, secret. Even within the company, very few were permitted to see it.

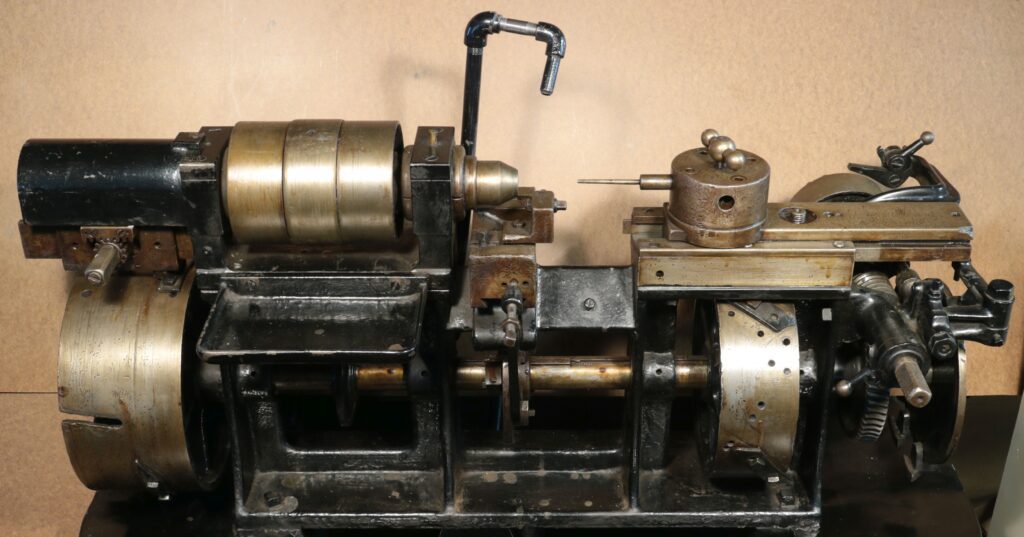

The first commercially available automatic lathe, the Spencer automatic was patented and first marketed in 1873.

Comparing the two machines, the first thing that stands out is that although the Vander Woerd machine is making smaller parts, it is much, much more solid. Christopher Miner Spencer (1833 – 1922)was later a partner with C. E. Billings (1834 – 1920), who apprenticed at R&L and was born in Weathersfield, just down the road.

The Spencer machine can do a much wider variety of work. The Vander Woerd really shines at its job of making watch screws, but wouldn’t do well at much else.

The Vander Woerd machine also does an operation the Spencer can’t. It slots the screw head, which is a milling function.

Some machinery was greeted with great suspicion in the 19th century by workers who feared that their jobs would be eliminated. Some of the men doing the work taken over by this machine may have been relieved. The operators of hand-controlled lathes producing watch screws, with the help of a boy moving material for them, could turn out as many as 1,500 tiny screws in a day. It must have been extremely demanding work.

The fully automatic machines could make as many as 8,000 to 10,000 screws a day, and a well-trained operator could run as many as a half-dozen automatics.

Our machine is one of the first 45 to be made. These early machines are distinguished by the fine quality of their finish. Most later machines were only copies of the originals and just aren’t of such high grade.

Our machine is missing several parts. We have a contact who is looking forward to replacing them. It’s also possible that he may be able to arrange for the machine to be running.

So how does it work?

A series of circular cams and followers convert rotary motion into linear motion.

-

- A collet in the headstock holds the wire rod used to produce the screw. The wire rod passes through the collet when opened.

- Once in position, the collet closes and holds the wire rod.

- As the rod spins, a series of tools engage the material to form the thread and head of the screw.

- The pick-off tool swings down from the rear of the lathe and receives the nearly-finished screw as the cut-off tool parts it from the wire. Then the pick-off tool carries the screw to a station where a tiny circular saw swings down and cuts a slot in the head of the screw.

- Once completed, the screw is dropped into a small container under the slotting station, and the process repeats.

YouTube has videos of Vander Woerd machines actually running: here’s one, courtesy of the Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation

stay up to date

Want more content from the American Precision Museum?

Sign up to receive news straight to your inbox!